A few days ago I shared some suggestions about ways to relive the events of April 19, 1775. Before April 19th gets too far in our rear view mirror, I want to offer a few thoughts about another momentous event in American history that occurred on that date. If you read any news feeds at all on the 19th, you probably already know what I have in mind.

It was twenty years ago Sunday that twenty-six-year-old army veteran Timothy McVeigh parked a rental truck packed with homemade explosives in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. The subsequent explosion at 9:02 a.m. killed one hundred sixty-eight men, women, and children and injured more than six hundred others. The atrocity was, and remains, the costliest act of domestic terrorism in U. S. history.

By his own account, McVeigh’s choice to strike on the 19th of April had nothing to do with the events at Lexington and Concord two hundred twenty years earlier. April 19, 1995 was the second anniversary of the fiery culmination of a 51-day standoff in Waco, Texas between federal agents and the followers of Branch Davidian cult leader David Koresh. McVeigh committed mass murder to protest what had happened there, and as a “counterattack” against a federal government which, in his twisted view, was already at war against its citizens.

And yet a connection between the events still calls out. For several years before the bombing, McVeigh had immersed himself in a gun-show culture that often drew parallels between its adherents and the patriots of 1776. What is more, McVeigh had taken to memorizing passages from the writings of patriot leaders, and when he was arrested within ninety minutes of the bombing, he was wearing a t-shirt with this sobering quote from Thomas Jefferson: “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” Thus it may have been a coincidence that McVeigh struck his purported blow for liberty on the day that most historians date as the beginning of the American Revolutionary War, but McVeigh would surely have thought it a happy coincidence.

This is why Timothy McVeigh will always be linked in my mind with Thomas Jefferson and the Lexington Minutemen. I only wish that McVeigh could have understood both better.

First, regarding Jefferson: The quote that McVeigh wore on his back as he positioned explosives underneath a daycare center has to be understood in context. Let me be clear before I go farther: I’m not all that interested in defending Jefferson. To be honest, I’m not a big fan of the “Sage of Monticello.” He was brilliant, undoubtedly, but also deeply flawed. For someone who claimed all his life to be guided by reason, Jefferson was “capable of living with massive contradictions” when it came to his own belief and behavior (to quote his biographer, Joseph Ellis).

Jefferson declared that “all men are created equal” but owned one hundred fifty human beings as he penned those words. He championed democracy but lived a life of privilege and–for his day– almost unequaled luxury. He praised industry and frugality but denied himself nothing that his eyes desired. (When he returned to the states from several years’ service as ambassador to France, he brought with him more than one hundred crates of wine, artwork, books, and other souvenirs of his stay abroad.) He could be disingenuous to the point of duplicity, and he suffered from self-conceit that bordered on hubris. (The best example of the latter was his approach to the New Testament: taking scissors in hand, he purged the gospels of the slightest scent of the supernatural and turned Jesus into an Enlightenment philosopher. As one writer puts it, “by the time Jefferson was through with Jesus, Jesus looked a lot like Jefferson.”)

A final flaw of Jefferson’s–and this brings us back to the quote on McVeigh’s t-shirt–was a penchant for making irresponsible moral pronouncements that he never expected to see the light of day. I call them “irresponsible” because Jefferson made them with no expectation that he himself would have to live up to them. The “tree of liberty” comment is a case in point.

In context, Jefferson’s much quoted aphorism grew out of his concern about the likely fallout from Shay’s Rebellion. From his post in France, Jefferson received reports of how, beginning in the late summer of 1787, popular discontent had begun to percolate in rural Massachusetts. A depressed economy and a shortage of circulating currency was making it increasingly difficult for farmers to pay their property taxes. The “Rebellion” (named for one of several leaders, a war veteran named Daniel Shays) involved disgruntled small landowners marching on courthouses to prevent foreclosures and sheriff’s sales. The state militia confronted the rebels on two occasions in January and February 1787–killing five of their number and wounding a couple dozen more–and the protests waned rapidly thereafter.

Jefferson first heard of the commotion in late December 1786, when he received a letter from New York’s John Jay, who was then serving as Secretary of Foreign Affairs under the Articles of Confederation. Jay informed Jefferson that “a Spirit of Licentiousness has infected Massachusetts” and that this might soon prompt the majority to call for more vigorous government. Fearful of the mob, “the rational and well intentioned” portion of the population would become willing to trade “the Charms of Liberty” for “Peace and Security.” If the rebels continued to promote anarchy, Jay concluded, “Tyranny may raise its Head, or the more sober part of the People may even think of a King.”

At this point Jefferson was absolutely opposed to any effort to strengthen the central government, and in his correspondence he repeatedly emphasized that the uprising in Massachusetts was of trivial import. In no way should it justify a radical departure from the weak central government embodied in the Articles. “I was not alarmed at the humor shewn by your countrymen,” he wrote to Abigail Adams shortly before Christmas. “On the contrary, I like to see the people awake and alert.” The “commotions” in America “offer nothing threatening” he placidly informed the president of Yale College in a letter penned three days later. “If the happiness of the mass of the people can be secured at the expense of a little tempest now and then, or even of a little blood, it will be a precious purchase.”

A month later he shared his opinion with James Madison that “the late troubles in the Eastern states . . . do not appear to threaten serious consequences. . . . I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing,” Jefferson opined blithely. “It is a medicine necessary for the sound health of government.” And to Abigail Adams, who had written to inform Jefferson that he totally misunderstood the “Mobish insurgents” wreaking havoc in Massachusetts, Jefferson reiterated his view that “the spirit of resistance to government” must “be always kept alive.” In sum, he informed Abigail, “I like a little rebellion now and then.”

Later that year Jefferson’s worst fears were realized as he began to receive reports of the work of the Constitutional Convention meeting in Philadelphia. The most troubling revelation was that the assembly of “demi-gods” had agreed to allow the executive to be eligible for perpetual reelection. From France, Jefferson could smell the first whiff of a conservative counterrevolution; so soon liberated from the tyranny of George III, the nation was rushing to reestablish monarchy. Convinced that the new Constitution was a tragic overreaction to a trivial “tempest” in Massachusetts, he ratcheted upward the rhetorical intensity and bravado. Writing in November 1787 to John Adams’ son-in-law, William S. Smith, Jefferson blurted, God forbid we should ever be twenty years without such a rebellion. . . . What country can preserve it’s [sic] liberties if their rulers are not warned from time to time that their people preserve the spirit of resistance? Let them take arms. . . . The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.”

Far from an exhortation to future Timothy McVeighs, Jefferson was trying to influence the debate over the U. S. Constitution. Politics in 1787 was still a gentleman’s affair, and political campaigning still consisted primarily of privileged elites writing to other privileged elites in an effort to sway their opinion. His goal in this context was to minimize the perceived threat posed by Shays’ Rebellion, and he did this in two ways. First, he suggested that better education of the masses would make such uprisings more and more scarce. The rebels’ motives were “founded in ignorance,” he told Smith. Their acts were “absolutely unjustifiable,” he explained to James Madison. “The spirit of resistance to government . . . will often be exercised when wrong,” he conceded to Abigail Adams. I haven’t seen that on a t-shirt lately.

Second, he tried to reassure his correspondents that small-potatoes uprisings like Shays’ Rebellion were actually “proof that the people have liberty enough,” as he wrote to Yale president Ezra Stiles. In a free society, such expressions were occasionally to be expected. And what was the shedding of “a little blood,” the significance of “a few lives lost,” if it kept alive the spirit of liberty?

In our mind’s eye we need to see Jefferson writing such statements in his rented villa in the French countryside, seated at his writing table in slippers, sipping on sherry and waited on by servants (including Sally Hemings, who arrived with his eight-year-old daughter in June 1787). Jefferson was not the radical that Timothy McVeigh must have imagined. He was an armchair revolutionary at best, making bold statements about the shedding of blood without having to worry that any blood that might be shed to refresh the tree of liberty would be his own.

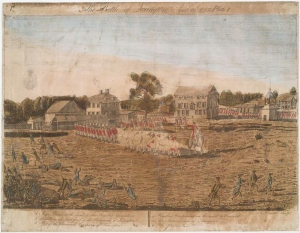

How different the fathers and sons who stood in the predawn cold at Lexington Green two hundred forty years ago this past Sunday! They were not Enlightenment Epicureans given to bold but hypothetical pronouncements. They were simply accustomed to governing themselves. In the aftermath of the Boston Tea Party the British Parliament had shut down their town meeting, and now British soldiers were invading the town itself. And so they had gathered on the common green to look the invader square in the eye, knowing full well what it might cost them. They waited for their enemy to fire first, and when they did, a fourth of the minutemen fell.

Their courage has inspired generations of Americans.

And no children died at their hands.

Dr. McKenzie, like you, I have problems with Thomas Jefferson. His behavior was often at odds with the image of himself he tried to project. However, to call him an arm chair revolutionary is not quite fair. He chose to join the fight against the British empire knowing full well that he would face permanent exile or hanging if his cause was lost. As governor of Virginia, he had direct involvement in military affairs. He was nearly captured at Monticello by forces under the command of Benedict Arnold. While one can criticize his lifestyle, its still accurate to say that he lost a lot economically by not siding with the British. While his remark about bloodshed can be justly criticized, he had every right to be concerned that all he had fought for was imperiled (in his opinion).

Pingback: THE YEAR IN REVIEW: WHAT YOU COULD HAVE READ HERE IN 2015 (BUT PROBABLY DIDN’T) | Faith and History

Interesting read….thanks for posting.