[This week marks the 153rd anniversary of the three-day-long Battle of Gettysburg, the largest battle of the American Civil War and the largest military engagement ever fought in the western hemisphere. With the anniversary in mind, I am re-posting a series of four essays that I originally penned two years ago after my first visit to the battlefield. The first was a kind of tourist’s report; the remaining three–including the concluding below–are more properly styled meditations or reflections. My goal in these was to explore what it might mean to remember that bloody conflict through eyes of faith.]

One of my favorite quotes about the value of history comes from historian David Harlan, who reminds us that, “at its best, the study of American history can be a conversation with the dead about what we should value and how we should live.” Not many academic historians hold to that view anymore, and we’re the poorer because of it. I was repeatedly reminded of this as I walked the ground at Gettysburg–the opportunities for life-changing conversations abound, if we have ears to hear. “Hear” is the key verb, because the conversations that I have in mind require above all that we be willing to listen.

Sometimes in such conversations the figures from the past interrogate us. The first conversation that I was drawn into was of this sort. It began as I tried to envision what happened there a century and a half ago, when over one hundred and fifty thousand soldiers in blue and gray clashed in the largest battle ever fought in the western hemisphere. I have previously noted the chasm that separates us from the men who fought there, and yet it is almost impossible to walk in their footsteps without imagining what it was like to be in their shoes. And as I clambered among the boulders at Devil’s Den, peered through the trees on Little Round Top, and ascended the long, gentle slope of Cemetery Ridge, the questions running through my mind began to change. When the conversation began, I was the one doing the asking–posing safe, academic questions about troop movements and tactics. But then as I tried to imagine what these men experienced, much more personal, far more disturbing questions came to dominate my thoughts.

“Could you steel yourself to do what these men did?” I found myself wondering. “Could you endure what they endured?” More importantly, “Could you witness such carnage and still believe in mankind? Could you help to inflict such destruction and still believe in yourself? Could you experience such suffering and still believe in God?” Above all, “Are you devoted to any principle, any cause, any person, any Master enough to give, in Lincoln’s words, “the last full measure of devotion?”

The short answer to all of the above is, “I don’t know.” I pray to God that my faith would not falter, but I just don’t know. What I do know about myself is not reassuring: I too often struggle with even the most trivial acts of self-denial, the most mundane expressions of laying down my life that pale in comparison to the price paid by so many who fought here.

Sometimes our conversations with the past involve listening in on a discussion among historical figures and trying to learn from it, trying to glean wisdom as to “what we should value and how we should live.” I was also drawn into this kind of conversation as I walked the ground at Gettysburg, particularly as I contemplated the nearly fourteen hundred monuments that are sprinkled across the landscape. As I’ve noted before, Gettysburg National Park is arguably the world’s largest statuary garden, and as such it speaks not only to the battle itself but also to its aftermath.

As with tombstones in a cemetery, we read in the ubiquitous inscriptions two kinds of testimony: testimony about the doings of men, and testimony about the longings of mankind. That is, their words speak not only to what happened here, but also to how the soldiers who are commemorated, as well as their descendants, yearned for significance and wanted to believe that their lives mattered. In this sense, the monuments at Gettysburg are best understood as part of an ongoing conversation about the meaning of what happened there, and that conversation is, in a sense, merely a small part of a universal human dialogue about why, or whether, our lives matter at all.

As I noted in my last post, in their language the vast majority of Gettysburg’s monuments are mundane. Like Mr. Gradgrind in Dickens’s Hard Times, they care for nothing but “the facts.” The company or regiment in question fought on this spot at this time for this objective. It sent this many men into battle and suffered this many casualties. But not all are so reticent. “It’s not enough to remember what these men did,” the exceptions seem to say. “Subsequent generations must also know why these men fought, and why we should venerate them.”

Modern-day historians such as James McPherson and Chandra Manning have read literally tens of thousands of pages of Civil War soldiers’ diaries and letters in an attempt to understand why men fought in the Civil War. The words they have pored over were not chiseled in granite but scribbled in pencil. In their unguarded moments, Civil War soldiers revealed a broad range of motives. Some voiced ideological motives. Speaking in terms of duty and obligation, they professed to have enlisted in order to defend liberty, or democracy, or union, or states’ rights, or republican government, or the legacy of 1776 (however they understood it). Others enlisted for less exalted reasons: to escape boredom, find adventure, prove their manhood, see the world, impress girlfriends (or potential girlfriends), increase their income, or avoid the draft.

The Gettysburg monuments that speak to the larger meaning of the battle see only what was noble. The prototype in this regard is one of the oldest and largest monuments on the field, the so-called “Soldiers’ National Monument” that rises from the heart of the national military cemetery just north of Cemetery Ridge. Dedicated in 1869, its primary inscription consists of the closing lines of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, with its ringing references to a “new birth of freedom,” “government of the people,” and those “who here gave their lives that [the] nation might live.”

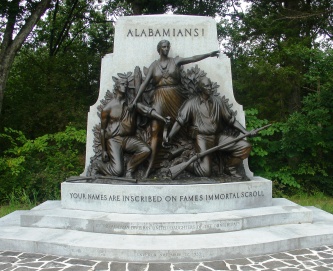

Most of the monuments erected at Gettysburg honor specific military units or particular individuals, but many of the states that were represented at Gettysburg eventually built state monuments as well, and these larger monuments regularly make claims about the object and meaning of their sons’ sacrifice. A sampling of state monuments tells us that Pennsylvanians fought for “the preservation of the Union.” Michigan troops were champions of “liberty and union.” Soldiers from Indiana–a state with more than its share of opposition to emancipation–fought for “equality” and to “advance freedom.”

Southern state monuments were often (understandably) less specific. Tennessee soldiers were guided by unspecified “convictions” and performed “their duty as they understood it.” Floridians “fought with courage and devotion for the ideals in which they believed”–whatever they were. Georgia’s Confederates, though, were forthrightly patriotic. (“When duty called, we came; when country called, we died.”) More explicit still, South Carolina soldiers were propelled by an “abiding faith in the sacredness of States Rights.”

I want to be clear here. I am not sneering at the possibility that many of those who fell on this field were motivated by high ideals. I am convinced that many were, and I admire them for it. C. S. Lewis has written that the greatest chasm separating the human race is not the divide between Christians and non-Christians or even that between theists and atheists, but rather the gulf between those who recognize any belief system outside of themselves that demands their allegiance and those who acknowledge no such standard. The latter, in the words of G. K. Chesterton, are adherents of “the most horrible” of religions: “the worship of the god within.” In a recent essay on the importance of fatherhood, N.Y.U. psychologist Paul Vitz observes that “the world is hungry for examples of unselfish men.” In our age of materialism and individualism, the example of those who did fight at Gettysburg for union or states’ rights, freedom or independence, is a breath of fresh air.

And yet we need to think carefully about the conversation that we are listening to. What impresses me most about these monuments is their use of religious language and imagery in commemorating the men who fought here. It’s not that there are references to God, Jesus, or Christian faith–I’ve found almost none. But think about the words and phrases that do appear: “martyrs,” “devotion,” “sacrifice,” “faith,” “immortal” fame, “righteous” causes, “eternal glory,” “the millennium of their glory,” “sacred” heritage, “no holier spot,” and “ground forever hallowed.” As with Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, such rhetoric confuses the sacred and the secular. It fuels a temptation to which none of us is immune: the temptation to conflate our identity as Christians with other loyalties and attachments.

But such language also speaks to a universal human longing. No one is truly, completely happy, Christian philosopher Peter Kreeft observes. Beneath the surface of our lives, with its innumerable distractions and diversions, “the deep hunger of [our] hearts remains unsatisfied.” We reflect on life and, in our unguarded moments, we are haunted by a recurring question: “Is this all there is?” The reason, Kreeft goes on to explain, is that “we are not supposed to be happy here.” This is not our home. “You made us for Yourself,” Augustine of Hippo concluded nearly sixteen centuries ago. “Our hearts find no peace until they rest in You.”

And yet we commonly cope with our heart hunger through self-deception, convincing ourselves that we can find meaning and purpose, fulfillment and transcendence in this life alone. As Christians, we are free to give a conditional loyalty to the state, but not our ultimate loyalty. All too often, the monuments at Gettysburg that speak to the battle’s larger meaning imply that we can be the authors of our own immortality, and that the key to our doing so lies in our making sacrifices to the state. Christian scholar Wilfred McClay has written recently that, because “human beings are naturally inclined toward religion . . . we have an incorrigible need to relate secular things to ultimate purposes.” Gettysburg’s monuments remind us that, because we are fallen, we are naturally tempted to equate secular things and ultimate purposes.

But these are not the only voices that I heard at Gettysburg, for there were countless others raised during the battle itself. Most of these cries from the heart are known only to God, but a fraction has survived in the soldiers’ own words, confessions made to contemporaries rather than declarations to posterity. One stands out in my mind, the testimony of an unnamed, unknown soldier who bore witness to a different kind of response to the indescribable happenings on this field.

We know of this soldier only through the recollection of another, Confederate Captain George Hillyer of the Ninth Georgia Infantry, a regiment in Anderson’s brigade of Hood’s division of Longstreet’s corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. Twenty-nine miles from Gettysburg when the fighting began on July 1st, they had marched all day and night and arrived on the field just before daylight on the 2nd. After spending the morning lying in a stand of woods due west of the Round Tops, in the afternoon Hillyer’s company was part of the general Confederate attack on the Union left. After making it almost to the base of Little Round Top, the Ninth Georgia was forced to withdraw, and Hillyer and his exhausted and bloodied company spent the night within earshot of Farmer Rose’s wheat field, a twenty-six-acre expanse that had been the site of some of the day’s fiercest fighting. As the sun went down, the wheat field was a kind of “no-man’s land” between the contending armies, with perhaps as many as four thousand dead and wounded soldiers now carpeting the flattened grain.

And in the midst of that hellish scene, Hillyer marveled to hear one of the men between the lines begin to sing. “He was probably a boy raised in some religious home in the South,” Hillyer recalled later, “where the good old hymns were the standard music.” There were “thousands of desperately wounded men lying on the ground within easy hearing of the singer,” the captain observed, “and as his voice rang out like a flute . . . not only the wounded, but also five or ten thousand and maybe more of the men of both armies could hear and distinguish the words.” The lines that they heard had been penned four decades earlier by an Irish poet named Thomas Moore and then set to music and published in 1831:

Come, ye disconsolate, where’er ye languish; / Come to the mercy seat, fervently kneel; / Here bring your wounded hearts, here tell your anguish; / Earth has no sorrow that heav’n cannot heal.

This is the voice that I will remember most from my visit to Gettysburg. To take the past seriously is to put our own lives to the test, and the conversations at Gettysburg do just that, pressing us with hard, discomfiting questions: What do we value? In what do we hope? Where do we find meaning? The answers etched here in granite are noble, but they are also earthbound, temporal. Far more challenging, far more convicting, far more comforting, far more hopeful is the response on the lips of this unknown soldier. Sung in darkness amid death and despair, it is both historical occurrence and spiritual metaphor, an echo of God’s invitation to a bruised and hurting world.

Come to the mercy seat, fervently kneel . . .

Dr. McKenzie,

With so much in the news recently about cities and locales throughout the south embroiled in bitter conflicts in the courts over the removal of statues and memorials to the Confederacy and honoring many of the leaders of the South from the Civil War, I was drawn back to your reflections last year of your time at Gettysburg. In re-reading these posts, I detect now that you, like me as a fellow southerner (I was raised in Mobile and am a loud & proud Crimson Tide graduate), have a sense of conflict over our home region. I would be curious to hear your thoughts, as an historian, how to reconcile our love for the region of the country that formed us and the conflict in today’s America over the past that is innate to our identity as southerners?

Since the day I packed my car in 1980 and left Alabama, first for Texas and eventually to Illinois, there is still very much as sense that “my home’s in Alabama…” and I feel a sense of pride and loyalty as a southerner. However, I do not embrace this heritage with a sense of blind loyalty that tries to ignore or downplay the sins of our past. Southern history, sadly, will always bear the indelible stain of slavery – a stain that continues to cause deep division and is at the root of many of the conflicts that continue to burden racial and regional relationships in America. And yet, much like my ancestors who fought in the war out of a sense of duty and loyalty to the place they considered ‘home’ – whether a state (such as Lee felt for Virginia) or a region – I feel, in my heart, a similar sense of loyalty. Often, when asked even today, where I’m from – my answer is never “Illinois” where I’ve lived for the past 20 years, but, instead, I will answer, “Alabama” or “my home is in the southern U.S.” My wife, who is Canadian, has often remarked on this and asked, “why do you still say you’re from Alabama?”

After re-reading this post from your 2016 trip, I think you have hit upon some of the root of my feelings & emotions – a sense of “place”, of “belonging”, of a commitment to “something”. How do we convey this without sounding as if we are apologists for the sins of our past? I find now that with many of my black friends whom I’ve known since childhood in Alabama in the 60’s – to voice my sense of pride as a southerner is no longer met with “welcome” but I am suddenly grouped with “alt-right” racism… something that is far from my convictions!

I welcome your thoughts…

Dear Tom: What a profound question! You’ve hit on something that I indeed struggle with. Let me give this some more thought before answering. I’ll be back in touch.

I look forward to your thoughts… I’d love to have an opportunity this summer, if you’re open to this, to meet for coffee. I live only about 20 minutes from the college.

Love my visits to GB …A 5 star post…thank you

Sent from my iPhone

>