Last week was political primary week in Illinois, and that means that the stretch run to the general election this November is now officially underway. I’ve been at Wheaton College for nearly four years now, long enough to conclude that Illinois voters are more cynical than most I’ve encountered. I suppose you get that way when state governors regularly end up in jail and convicted felons are serious contenders for the Chicago board of aldermen. (Riddle: You’re sitting in a room with a former Illinois governor to your left and another former Illinois governor to your right. Where are you? Answer: Prison.)

Simultaneously ignoring and feeding such widespread cynicism, the day after the primary the Chicago Tribune repeatedly warned readers that the campaign for governor will be brutal. “The Brawl Is On” proclaimed the page-one headline (Chicago Tribune, March 19, 2014). “It’s going to be ugly,” an editorial agreed, quoting an unnamed senior Illinois politician. Not one, but two front-page “news” stories told voters what to expect. It will be a “particularly contentious,” “bruising fight,” short on serious reflection, long on “raw emotion,” and punctuated by a slew of “scorched-earth attacks.”

In a word, the style of the campaign promises to be vicious. The campaign’s substance—if it can be said to have any—will be populist. The word populist comes from a Latin root meaning “people.” When applied to politics, the word connotes a relentless emphasis on the people (always vaguely defined) and threats to their well being (whether real or invented). Populist politicians present themselves as one of “the people,” portray their opponents as out of touch with “the people,” and define political questions as a struggle between “the people” and the elites and “special interests” who would exploit them. In the months to come there will be countless charges and countercharges about concrete political issues, e.g., the state’s debt crisis, rising tax rates, the death penalty, and gay marriage, to name only a few. But one issue will both permeate and transcend all others: which candidate will be more responsive to “the people”? Or more simply, which candidate is more truly one of “us”?

Both gubernatorial candidates will lay claim to the title of the people’s champion, although not necessarily in the same way. As the Tribune observes, the campaign “will feature dueling brands of populism.” The Republican challenger’s “style of populism is the classic throw-the-bums-out.” The GOP nominee, a wealthy businessman named Bruce Rauner, is already denouncing the Democratic incumbent as a “career politician” held captive by special interests. Chief among these are the powerful state employee unions, supposedly gorging on padded salaries and bloated pensions funded at taxpayer expense. The people of Illinois, so the Republican message goes, are the victims of an unholy alliance of “union leaders and establishment politicians.”

The Democratic populist response, according to the Tribune, will be to declare “class war.” The sitting governor, Democrat Pat Quinn, is already denouncing his wealthy challenger as “out of touch” with the working class, “the real everyday heroes of our state.” “I believe in everyday people,” Quinn noted in his victory speech after the polls closed. “I’m not a billionaire.” (The Rauner camp denies that their man is that wealthy, but the alliteration of the epithet “Billionaire Bruce” is too much for the Quinn campaign to pass up.)

The Tribune is almost certainly correct in its predictions. The campaign will be a street fight. And its primary message—its all pervasive message—will be populist. Because I am a historian, however, I think that historical perspective can help us in thinking about this present moment. There is nothing new about vicious, populist campaigns in American politics. Indeed, they appeared on the scene pretty much simultaneously with the rise of American democracy. If anything, twenty-first-century elections are dignified and well-mannered in comparison with those of two centuries ago.

I am mindful of this because my class on U. S. History here at Wheaton has just finished an in-depth review of the presidential election of 1828. The 1828 election was an important transitional milestone in American political and cultural history. It is easy to overstate the case, but it is not too much of an exaggeration to describe politics prior to the 1820s as a gentlemen’s affair. By the culmination of that decade, however, the political world as we know it was coming into focus.

In colonial America, political campaigns—at least as we would define them today—did not exist, nor did formal political parties. On election day, eligible voters (i.e., white male landowners) would congregate at the county seat and learn which of the local gentry had agreed to “stand” for office. According to custom, the candidates would rarely speak on their own behalf. An individual who desired office was presumed to be power-hungry, and thus disqualified from the public trust. The absence of speeches was made up by a great deal of drinking, however, since custom dictated that the wealthy nominees “treat” the voters to large quantities of free alcohol.

When George Washington was a candidate for the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1758, for example, his personal papers reveal that he supplied voters with 28 gallons of rum, 50 gallons of rum punch, 34 gallons of wine, 46 gallons of beer, and two gallons of “cider royal.” (This amounted to a total of 160 gallons for 391 registered voters, or about 1 1/2 quarts per voter.) A few years later, James Madison, the future father of the U. S. Constitution, also ran for the House of Burgesses but followed a different strategy. Madison was disturbed by “the corrupting influence of spirituous liquors.” He viewed the tradition of “treating” voters as “inconsistent with the purity of moral and republican principles.” The future U. S. president was committed to “a more chaste mode of conducting elections” and declined to treat voters. He was defeated.

Beyond the flowing alcohol, the most prominent feature of colonial elections was how deferential and personal they were. Voters took for granted that candidates would come from the social elite—the oldest and wealthiest families. And because there were no established political parties in colonial America—and no party platforms—almost the only “issues” in an election involved the character of the candidates involved.

To put it differently, colonial politics was largely a politics of reputation. According to the dominant political values of the day, the only non-negotiable prerequisite for public office was virtue—the willingness to sacrifice self-interest for the common good. And because it was assumed that the local elites who stood for office would frequently understand political issues more thoroughly than their neighbors (thanks to superior education and the leisure time necessary to stay well-informed), it was assumed that virtuous officeholders would sometimes have to contradict the wishes of their constituents.

This view of politics informed the earliest presidential elections after the ratification of the Constitution. If anything, they were more elitist than the colonial pattern described above. The delegates to the 1787 Constitutional Convention made no explicit allowance for popular involvement in the election of the nation’s executive. The president was to be chosen by the vote of the Electoral College, and the implicit expectation was that the electors who composed this bizarre institution would be prominent statesmen appointed by the various state legislatures. The executive, in other words, would be identified by the vote of a comparative handful of prominent men. (Only sixty-nine electors cast ballots when George Washington became the first U. S. president in 1789.)

And so in 1796—after George Washington announced only two months before the election that he would not stand for a third term as president—the presidential “campaign” that ensued primarily involved prominent men writing private letters to other prominent men about the qualifications of the leading contenders, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Four years later—when the same two statesmen again squared off—the same elitist air survived but had weakened. In addition to writing letters, interested statesmen were now more willing to write public pamphlets, and the country’s small but growing number of newspaper editors was beginning to weigh in as well. The times were changing.

Yet as late as 1824 the aristocratic tone of presidential elections largely survived. State laws had changed in the intervening quarter century, so that now most presidential electors were to be popularly elected rather than appointed by the state legislatures. Even so, scarcely a fourth of eligible voters bothered to cast ballots in 1824, and campaign managers for the various candidates still assumed that the “public opinion” that needed to be courted was the opinion of the wealthy and powerful. For their part, the rest of the electorate seemed not to care.

This changed in 1828. Describing the change is easy. The number of votes cast more than tripled, and all across the United States a much broader swath of adult white males paid attention to national politics than ever before. Why this occurred is a complicated question. There were several factors at play, but for our purposes, one factor is paramount: the outcome of the 1824 election and the way that one candidate and his supporters responded to it.

The 1824 election had actually played out pretty much the way that the framers of the Constitution had expected most elections to unfold. First of all, there had been a large number of serious candidates: Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, of Georgia; Kentuckian Henry Clay, Speaker of the House of Representatives; Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, of Massachuetts; and Major General Andrew Jackson, of Tennessee. Second, as might be expected in the absence of well-defined political parties, all of the candidates had attracted more of a regional than a national following. Third, and predictably given such a large field of candidates, no individual had received a majority in the Electoral College, which meant that the outcome had to be determined by a run-off election among the top three finishers in the House of Representatives. (Clay, who finished fourth, was the odd man out.) Finally, in the run-off in the House the congressmen had cast their ballots without necessarily feeling constrained by the popular vote in their home states. Although many did so, overall they favored the second-place finisher, Adams, over the first-place finisher, Jackson. There was nothing unconstitutional about their doing so, and nothing necessarily insidious in their decision that Adams was the more qualified. (In terms of political experience, he unquestionably was.)

The 1824 election had actually played out pretty much the way that the framers of the Constitution had expected most elections to unfold. First of all, there had been a large number of serious candidates: Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, of Georgia; Kentuckian Henry Clay, Speaker of the House of Representatives; Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, of Massachuetts; and Major General Andrew Jackson, of Tennessee. Second, as might be expected in the absence of well-defined political parties, all of the candidates had attracted more of a regional than a national following. Third, and predictably given such a large field of candidates, no individual had received a majority in the Electoral College, which meant that the outcome had to be determined by a run-off election among the top three finishers in the House of Representatives. (Clay, who finished fourth, was the odd man out.) Finally, in the run-off in the House the congressmen had cast their ballots without necessarily feeling constrained by the popular vote in their home states. Although many did so, overall they favored the second-place finisher, Adams, over the first-place finisher, Jackson. There was nothing unconstitutional about their doing so, and nothing necessarily insidious in their decision that Adams was the more qualified. (In terms of political experience, he unquestionably was.)

But neither Jackson nor his supporters ever accepted the validity of the outcome. Jackson had finished first in the popular vote (with about 43% of the total) and nothing else mattered. Days later their anger turned to outrage, when president-elect Adams named Henry Clay as his future secretary of state. Because Clay had cast his support to Adams on the eve of the run-off, Jackson and his supporters concluded that there had been a backroom deal, that Adams had bought off the Kentuckian with the promise of a plum post in his administration. Although no “smoking gun” ever proved the (probably false) allegation, the Jackson camp screamed “Corrupt Bargain!” and the charge stuck.

Although Adams and Clay were both supposedly parties to the dastardly deed, the Jacksonians reserved their greatest scorn for Clay, whom Jackson privately labeled “the Judas of the West.” Clay had justified his support of Adams by questioning Jackson’s fitness for the presidency. The Tennessean was a “military chieftain,” Clay had declared in a public letter, and history was full of military leaders who had begun as heroes and ended as tyrants. The House Speaker strongly implied that a Jackson presidency would end in the downfall of the republic, and his conscience would not allow him to stand idly by if it was within his power to prevent such a tragedy.

In this 1825 letter to a political ally, Jackson wrote of Clay: “The Judas of the West has closed the contract and will receive the thirty pieces of silver.”

“Hypocrite!” cried Jackson supporters. “The selfish ambition of Henry Clay is visible in every line of his letter,” cried the pro-Jackson Washington Gazette. “It is but a thin disguise to a foul purpose.” Back in Nashville, a livid Jackson agreed, writing to a political ally that “demagogues” were bartering the interests of the people “for their own views, and personal aggrandizement.”

Clay’s greatest alleged crime was neither hypocrisy nor political ambition, however. His chief offense, thundered the editor of the Gazette, was that he had “insulted and struck down the majesty of the People”; he had “impugned their sovereignty”; he had “gambled away the[ir] rights.” Jackson concurred. “The will of the people has been thwarted,” he wrote to an ally in 1825. “The voice of the people has been disregarded.”

Four years later, Jackson would have the chance to vindicate both himself and the “majesty of the people.” He was again a candidate for president, this time in a head-to-head match-up against the incumbent Adams. The 1828 presidential contest would be one of the dirtiest campaigns in history. One historian of the election has written that it may have “splattered more filth in more different directions and upon more innocent people than any other in American history.” As with earlier presidential elections, it was a campaign of personalities. What was new in 1828 was how public the charges and countercharges would be.

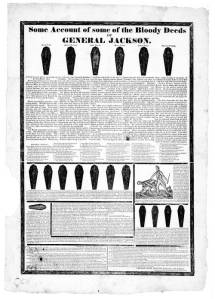

Four years earlier, Henry Clay had hinted that Andrew Jackson could not be trusted. In 1828, his political rivals went much further. John Quincy Adams’ supporters condemned the general in no uncertain terms: Jackson was the son of a prostitute and a slave, they announced; he was an adulterer, and he was a murderer. The adultery charge was dredged up from more than three decades earlier, when Jackson had unwittingly married supposed divorcee Rachel Donelson on the Tennessee frontier before her divorce had been officially approved by the Kentucky state legislature. The murder charge referred disingenuously to executions that Jackson had ordered during his military career. The Adams camp highlighted the latter with an infamous broadside now remembered as the “Coffin Handbill,” a poster featuring some seventeen coffins in silhouette, one for each man the blackguard Jackson had supposedly cut down in cold blood over his lifetime.

The Jackson campaign counterattacked with admirable creativity. They led with the accusation that Adams had stolen the presidency four years earlier, a claim valued less for its truthfulness than for its effectiveness. Beyond that, their strategy was clearly to show that the incumbent president was an effete intellectual out of touch with the common man. Adams was a Harvard graduate who spoke multiple languages and boasted an extensive record of public service. He had served as both congressman and senator from Massachusetts; as ambassador to the Netherlands, Prussia, and Russia; as Secretary of State; and now, of course, he occupied the White House.

John Quincy Adams’ silk underwear disqualified him for the presidency, in the view of Jackson supporters.

Jackson’s supporters turned these assets into aliabilities by denouncing Adams as a career politician, a child of privilege (son of President John Adams) who had never held a job that wasn’t handed to him. What was worse, his prolonged residence in European courts had corrupted his character and addicted him to debilitating luxury. As evidence of the latter, the Jacksonians cited Adams’ use of taxpayer money to buy a pool table and chess set for the White House, as well as his purported fondness for wearing silk “inexpressibles.” (How they knew what kind of underwear the president wore they never made clear.)

Jackson, in contrast, had been born into poverty in the southern Backcountry. His father had died before he was born, and the subsequent death of his mother and brothers from smallpox left him an orphan as a young teenager. He had almost no formal education and not too much regard for those who did. (A notoriously abysmal speller, he is supposed to have said that he couldn’t trust a man who could only spell a word one way.) What is more, Jackson had precious little political experience. He had twice been elected to Congress, and both times he had left the capital in disgust in a matter of months. When the Adams campaign ridiculed his lack of qualifications, however, the Jacksonians had the perfect, quintessentially populist retort: “Who would you rather have as president?” they asked. “Adams who can write . . . or Jackson who can fight?”

Fifty-six percent of voters chose the fighter.

We’ll discuss the implications of that decision next time.