It’s been a week since Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump delivered his own personal “Gettysburg Address.” As a historian who has taught and written about the American Civil War for three decades, I have been itching to respond, but free moments have been hard to come by. As it is, I don’t have time to craft a real essay, so the scattered reactions below will have to do for now.

First, the Trump campaign’s choice of Gettysburg for a major policy speech was risky at best. As press coverage of the event has underscored, Americans tend to think of Gettysburg as a sacred space—“hallowed ground”—and there was always the possibility that even sympathetic voters might recoil at the use of a locale where thousands gave their lives as a stage prop for a partisan stump speech. Furthermore, the location invites—no, demands—explicit comparisons between Lincoln and Trump, and one wonders whether Trump’s staff really thought that those would work in Trump’s favor. (That Trump himself thinks so he has already made clear.)

Questioned before the event about the choice of locale, an aide said that Trump “has spoken before about Abraham Lincoln” and that “Abraham Lincoln is going to be an important figure in terms of Mr. Trump’s vision for the Republican Party.” This is scary, given how little Trump seems to know about our sixteenth president. Has anyone forgotten his deer-in-the-deadlights answer to columnist Bob Woodward this past spring? Noting that Trump was poised to become standard bearer for the “party of Lincoln,” he asked the presumptive nominee why Lincoln succeeded. “Thought about that at all?” Woodward queried.

Trump would have been better off answering honestly, “No, I haven’t thought about that for an instant.” Instead, he gave the following non-answer:

Well, I think Lincoln succeeded for numerous reasons. He was a man who was of great intelligence, which most presidents would be. But he was a man of great intelligence, but he was also a man that did something that was a very vital thing to do at that time. Ten years before or 20 years before, what he was doing would never have even been thought possible. So he did something that was a very important thing to do, and especially at that time.

I’m glad we got that cleared up.

Trump aides also identified other motives for the Gettysburg locale in addition to Trump’s admiration of Lincoln (for doing that thing that he did). The battlefield is a symbol of sacrifice, they explained, which made the location both an ideal spot to honor veterans and to make a plea for unity.

This brings me to my second thought: both defenders and critics of Trump contend that Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address was all about unifying the country. Critics have especially stressed this idea, juxtaposing Lincoln’s supposed appeal for reconciliation and unity at Gettysburg with Trump’s divisive rhetoric.

Was Lincoln’s rhetoric at Gettysburg aimed at unifying Americans? Not really. He wasn’t remotely offering any olive branches to the one-third of the nation currently at war with his authority. A year and a half later, when Union victory was imminent, he would do exactly that in his Second Inaugural Address of March 4, 1865, but that was not his goal at Gettysburg. The interpretation of the war that Lincoln offered there was abhorrent to the white Southerners. He didn’t expect them to agree with his speech, but what is more, he didn’t expect them to hear it. Lincoln’s effective audience at Gettysburg was the North, not the entire country.

OK, then can we say that Lincoln was at least trying to unify the North in his remarks at Gettysburg? It depends on what you mean by “unify.” Did he search for common ground that all northerners could agree to? No. Did he make the most eloquent case that he could for a partisan policy and try to avoid unnecessarily offending his political opponents? I think so.

As Lincoln spoke, the North was split right down partisan lines for and against emancipation; the Republican Party supported it, while the Democratic Party unanimously denounced it. Like so many other politicians before and since, Lincoln used his public appearance before a large crowd as an opportunity to make a political statement. Even though he never once referred to emancipation explicitly, he wasted no time in defending his administration.

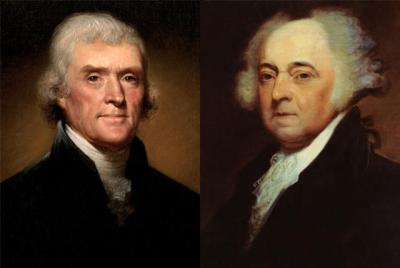

Lincoln’s argument was essentially historical. At worst misleading, at best debatable, it rested on a highly selective reading of the country’s founding. For years Lincoln had been insisting that his desire to end slavery was in keeping with the original vision of the Founding Fathers. “The fathers of the government expected and intended the institution of slavery to come to an end,” he proclaimed repeatedly during the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858. In advocating the restriction of slavery and its ultimate demise, Lincoln informed the audience that “I have proposed nothing more than a return to the policy of the fathers.” Lincoln’s view was a libel on the Founders, Democrat Douglas rejoined. Offering his own reading of American history, Douglas informed cheering Democrats that “our fathers made this government divided into Free and Slave States, recognizing the right of each to decide all its local questions for itself.”

And so when Lincoln began by telling the assembled throng at Gettysburg that our fathers had been “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” the politically savvy among them immediately recognized a familiar refrain in a long-standing partisan debate. And when, a couple of minutes later, Lincoln concluded his brief remarks by implying that the Union dead at Gettysburg had died so that the nation might have “a new birth of freedom,” the crowd understood that he was enlisting the fallen at Gettysburg in the controversial cause of emancipation.

Republicans saw nothing exceptional in this. Democrats were livid. The Harrisburg [PA] Patriot and Union concluded that the entire event “was gotten up more for the benefit of [Lincoln’s] party than for the glory of the nation and honor of the dead. The Chicago Times went further, reminding readers that it was to uphold the Constitution “and the Union created by it, that our officers and soldiers gave their lives at Gettysburg.” What the president had done at Gettysburg was simply despicable. “How dare he,” thundered the Times editor, “standing on their graves, misstate the cause for which they died, and libel the statesmen who founded the government? They were men possessing too much self-respect to declare that negroes were their equals, or were entitled to equal privileges.”

Today we don’t read the Gettysburg Address as a partisan speech in part because we read it in a vacuum. In chiseling it in marble, we’ve also wrenched it from its historical context. But we also don’t pick up on its partisanship because Lincoln himself did a good job of hiding it from posterity. There are no explicit cues for later generations. He never refers to his political opponents. He takes no cheap shots. His interpretation of the war was effectively the Republican interpretation of the war, but he hoped that someday all Americans would remember it in the same way and so he avoided gratuitous insults of those who disagreed with him.

Which leads me to one final thought: Lincoln rarely referred to himself in his public addresses. At Gettysburg, he never even uttered the word “I.” Although Trump’s aides promised that his speech would build on Gettysburg as a symbol of sacrifice and unity, Trump immediately focused on himself, branding those who have accused him of sexual impropriety as liars and promising to sue them just as soon as he is elected. Make of that what you will.