Only ONE more day until Thanksgiving. My goal this week has been to point out positive lessons we might learn from a more accurate encounter with the Pilgrims’ story. Today I tackle the question of why the Pilgrims really came to America and what we might learn from their experience.

**********

“Departure of the Pilgrims from Delft Haven,” Charles Lucy, 1847

The belief that the Pilgrims came to America in search of religious freedom is inspiring, but in the sense that we usually mean it, it’s not really true. I’ve shared this reality numerous times since writing The First Thanksgiving: What the Real Story Tells Us about Loving God and Learning from History, and I almost always get pushback from the audience. That’s understandable, since most of us from our childhood have been raised to believe quite the opposite. But if we’re going to really learn from the Pilgrims’ story, we need to be willing to listen to them instead of putting words into their mouths.

One of my favorite all-time quotes is from Democracy in America where Alexis de Tocqueville observes, “A false but clear and precise idea always has more power in the world than one which is true but complex.” The Pilgrims’ motives for coming to America is a case in point.

The popular understanding that the Pilgrims came to America “in search of religious freedom” is technically true, but it is also misleading. It is technically true in that the freedom to worship according to the dictates of Scripture was at the very top of their list of priorities. They had already risked everything to escape religious persecution, and the majority never would have knowingly chosen a destination where they would once again wear the “yoke of antichristian bondage,” as they described their experience in England.

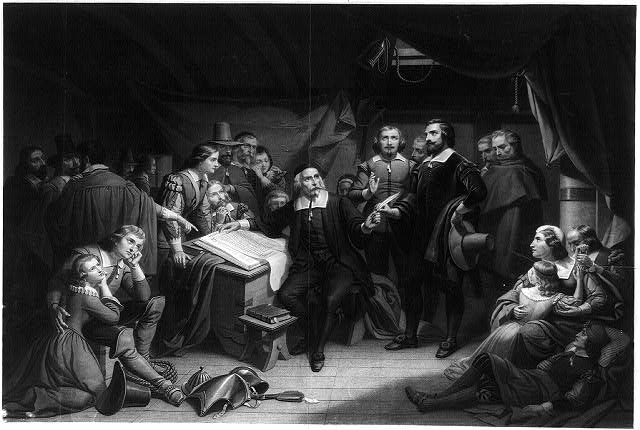

To say that the Pilgrims came “in search of” religious freedom is misleading, however, in that it implies that they lacked such liberty in Holland. Remember that the Pilgrims did not come to America directly from England. They had left England in 1608, locating briefly in Amsterdam before settling for more than a decade in Leiden. If a longing for religious freedom alone had compelled them, they might never have left that city. Years later, the Pilgrim’s governor, William Bradford, recalled that in Leiden God had allowed them “to come as near the primitive pattern of the first churches as any other church of these later times.” As Pilgrim Edward Winslow recalled, God had blessed them with “much peace and liberty” in Holland. They hoped to find “the like liberty” in their new home.

“Landing of the Pilgrims,” Henry A. Bacon, 1877

But that is not all that they hoped to find. Boiled down, the Pilgrims had two major complaints about their experience in Holland. First, they found it a hard place to raise their children. Dutch culture was too permissive, they believed. Bradford commented on “the great licentiousness of youth” in Holland and lamented the “evil examples” and “manifold temptations of the place.” Part of the problem was the Dutch parents. They gave their children too much freedom, Bradford’s nephew, Nathaniel Morton, explained, and Separatist parents could not give their own children “due correction without reproof or reproach from their neighbors.”

Compounding these challenges was what Bradford called “the hardness of the place.” If Holland was a hard place to raise strong families, it was an even harder place to make a living. Leiden was a crowded, rapidly growing city. Most houses were ridiculously small by our standards, some with no more than a couple hundred square feet of floor space. The typical weaver’s home was somewhat larger. It boasted three rooms—two on the main floor and one above—with a cistern under the main floor to collect rainwater, sometimes side by side with a pit for an indoor privy.

In contrast to the seasonal rhythms of farm life, the pace of work was long, intense, and unrelenting. Probably half or more of the Separatist families became textile workers. In this era before the industrial revolution, cloth production was still a decentralized, labor intensive process, with countless families carding, spinning, or weaving in their own homes from dawn to dusk, six days a week, merely to keep body and soul together. Hunger and want had become their taskmaster.

This life of “great labor and hard fare” was a threat to the church, Bradford repeatedly stressed. It discouraged Separatists in England from joining them, he believed, and tempted those in Leiden to return home. If religious freedom was to be thus linked with poverty, then there were some—too many—who would opt for the religious persecution of England over the religious freedom of Holland. And the challenge would only increase over time. Old age was creeping up on many of the congregation, indeed, was being hastened prematurely by “great and continual labor.” While the most resolute could endure such hardships in the prime of life, advancing age and declining strength would cause many either to “sink under their burdens” or reluctantly abandon the community in search of relief.

In explaining the Pilgrim’s decision to leave Holland, William Bradford stressed the Pilgrim’s economic circumstances more than any other factor, but it is important that we hear correctly what he was saying. Bradford was not telling us that the Pilgrims left for America in search of the “American Dream” or primarily to maximize their own individual wellbeing.

“Pilgrims Going to Church,” George H. Boughton, 1867

In Bradford’s telling, it is impossible to separate the Pilgrims’ concerns about either the effects of Dutch culture or their economic circumstances from their concerns for the survival of their church. The leaders of the Leiden congregation may not have feared religious persecution, but they saw spiritual danger and decline on the horizon.

The solution, the Pilgrim leaders believed, was to “take away these discouragements” by relocating to a place with greater economic opportunity as part of a cooperative mission to preserve their covenant community. If the congregation did not collectively “dislodge . . . to some place of better advantage,” and soon, the church seemed destined to erode like the banks of a stream, as one by one, families and individuals slipped away.

So where does this leave us? Were the Pilgrims coming to America to flee religious persecution? Not at all. Were they motivated by a religious impulse? Absolutely. But why is it important to make these seemingly fine distinctions? Is this just another exercise in academic hair-splitting? I don’t think so. In fact, I think that the implications of getting the Pilgrims’ motives rights are huge.

As I re-read the Pilgrims’ words, I find myself meditating on Jesus’ parable of the sower. You remember how the sower casts his seed (the word of God), and it falls on multiple kinds of ground, not all of which prove fruitful. The seed that lands on stony ground sprouts immediately but the plant withers under the heat of the noonday sun, while the seed cast among thorns springs up and then is choked by the surrounding weeds. The former, Jesus explained to His disciples, represents those who receive the word gladly, but stumble “when tribulation or persecution arises for the word’s sake” (Mark 4:17). The latter stands for those who allow the word to be choked by “the cares of this world, the deceitfulness of riches, and the desires for other things” (Mark 4:19).

In emphasizing the Pilgrims’ “search for religious freedom,” we inadvertently make the primary menace in their story the heat of persecution. Persecution led them to leave England for Holland, but it was not the primary reason that they came to America. As the Pilgrim writers saw it, the principal threat to their congregation in Holland was not the scorching sun, but strangling thorns.

The difference matters, particularly if we’re approaching the Pilgrims’ moment in history as an opportunity to learn from them. It broadens the kind of conversation we have with them and makes it more relevant. When we hear of the Pilgrims’ resolve in the face of persecution, we may nod our heads admiringly and meditate on the courage of their convictions. Perhaps we will even ask ourselves how we would respond if, God forbid, we were to endure the same trial. And yet the danger seems so remote, the question so comfortably hypothetical. Whatever limitations we may chafe against in the public square, as Christians in the United States we don’t have to worry that the government will send us to prison unless we worship in the church that it chooses and interpret the Bible in the manner that it dictates.

Don’t misunderstand me. I’m not suggesting that we never ask the question. Posing it can remind us to be grateful for the freedom we enjoy. It may inspire us to greater vigilance in preserving that freedom and heighten our concern for Christians around the world who cannot take such freedom for granted. These are good things. But I am suggesting that we not dwell overlong on the question. I’m dubious of the value of moral reflection that focuses on hypothetical circumstances. Avowals of how we would respond to imaginary adversity are worth pretty much what they cost us. Character isn’t forged in the abstract, but in the concrete crucible of everyday life, in the myriad mundane decisions that both shape and reveal the heart’s deepest loves.

“First Thanksgiving at Plymouth,” Jeannie Brownscombe, 1914.

Here the Pilgrims’ struggle with “thorns” speaks to us. Compared to the dangers they faced in England, their hardships in Holland were so . . . ordinary. I don’t mean to minimize them, but merely to point out that they are difficulties we are more likely to relate to. They worried about their children’s future. They feared the effects of a corrupt and permissive culture. They had a hard time making ends meet. They wondered how they would provide for themselves in old age. Does any of this sound familiar?

And in contrast to their success in escaping persecution, they found the cares of the world much more difficult to evade. As it turned out, thorn bushes grew in the New World as well as the Old. In little more than a decade, William Bradford was concerned that economic circumstances were again weakening the fabric of the church. This time, ironically, the culprit was not the pressure of want but the prospect of wealth (“the deceitfulness of riches”?) as faithful members of the congregation left Plymouth in search of larger, more productive farms. A decade after that, Bradford was decrying the presence of gross immorality within the colony. Drunkenness and sexual sin had become so common, he lamented, that it caused him “to fear and tremble at the consideration of our corrupt natures.”

When we insist that the Pilgrims came to America “in search of religious freedom,” we tell their story in a way that they themselves wouldn’t recognize. In the process, we make their story primarily a source of ammunition for the culture wars. Frustrated by increasing governmental infringement on religious expression, we remind the unbelieving culture around us that “our forefathers” who “founded” this country were driven above all by a commitment to religious liberty.

But while we’re bludgeoning secularists with the Pilgrim story, we ignore the aspects of their story that might cast a light into our own hearts. They struggled with fundamental questions still relevant to us today: What is the true cost of discipleship? What must we sacrifice in pursuit of the kingdom? How can we “shine as lights in the world” (Philippians 2:15) and keep ourselves “unspotted from the world” (James 1:27)? What sort of obligation do we owe our local churches, and how do we balance that duty with family commitments and individual desires? What does it look like to “seek first the kingdom of God” and can we really trust God to provide for all our other needs?

As Christians, these are crucial questions we need to revisit regularly. We might even consider discussing them with our families tomorrow as part of our Thanksgiving celebrations.