Another year is coming to an end, and that always leads me to think about how short life is. Does that strike you as morbid? I used to be self-conscious about this preoccupation—it’s occurred to me that I don’t get invited to a lot of New Year’s Eve parties—but I’m past that now. I think the Scripture is pretty clear that reminding ourselves of the brevity of life is something we need to do regularly. It’s a practice that can help us to follow Christ more faithfully—provided that we respond to the reminder rightly.

But did you know that reminding ourselves of the brevity of life can also help us to be better historians? As a Christian historian, it delights me to see that an awareness that we live “in time” is crucial both to thinking Christianly and to thinking historically.

As I’ve argued before on this blog, we err when we define “Christian history” by its focus, making it synonymous with the history of Christianity—the study of Christian individuals, ideas, and institutions throughout the past. We also miss the mark when we define it by its conclusions. This has been one of the worst mistakes of the advocates of the Christian America thesis. Countless well meaning (but untrained) pastors and pundits have insisted that any authentically “Christian” history of the United States will determine that the United States was founded as a Christian nation by Christian statesmen guided by Christian principles. They condemn any interpretation that questions the determining influence of Christian belief as “secular,” “liberal,” “politically correct,” “revisionist,” or in some other way hostile to Christianity.

I want to suggest instead that Christian history is distinguished by the way of thinking that underlies it. In his book The Christian Mind, Harry Blamires defined thinking “Christianly” as a way of thinking that “accepts all things with the mind as related, directly or indirectly, to man’s eternal destiny as the redeemed and chosen child of God.” I’ll probably spend the rest of my life wrestling with what this requires of us, but here is what I think it means for the Christian student of history. Our study of the past will be but a subset of our larger call to “love the Lord with all our minds.” Our motive will be to understand God, ourselves, and the world more rightly, to the glory of God, the blessing of our neighbors, and the sanctification of our souls. Our approach will be to bring a Scriptural lens to bear on our contemplation of the past, keeping in mind all that the Bible teaches about the sovereignty of God and the nature and predicament of humankind.

This is where the brevity of life comes in. Both thinking Christianly and thinking historically requires us to be constantly mindful that we live in time.

So what does it mean to live “in time” as a Christian? I think it begins by daily reminding ourselves of one of the undeniable truths of Scripture: our lives are short. The Bible underscores few truths as monotonously. “Our days on earth are a shadow,” Job’s friend Bildad tells Job (Job 8:9). “My life is a breath,” Job agrees (Job 7:7). David likens our lives to a “passing shadow” (Psalm 144:4). James compares our life’s span to a “puff of smoke” (James 4:14). Isaiah is reminded of the “flower of the field” that withers and fades (Isaiah 40:7-8).

These aren’t exhortations to “eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die.” They are meant to admonish us–to spur us to wisdom, not fatalism. The psalmist makes this explicit in the 90th Psalm when he prays that God would “teach us to number our days, that we may gain a heart of wisdom” (Psalm 90:12, New King James version). To “number our days” means to remember that our days are numbered. They are depressingly few, even for the most long-lived among us. The Good News Translation is easier to follow here. It reads: “Teach us how short our life is, so that we may become wise.” Part of growing in Christian wisdom, it would seem, involves reminding ourselves that our lives are fleeting.

American culture, unfortunately, does much to obscure that truth. Compared with the rest of the world, most American Christians live in great material comfort, and for long stretches of time we are able to fool ourselves about the fragility of life. The culture as a whole facilitates our self-deception through a conspiracy of silence. We agree not to discuss death, we hide the lingering aged in institutions, and we expend billions to look younger than we are.

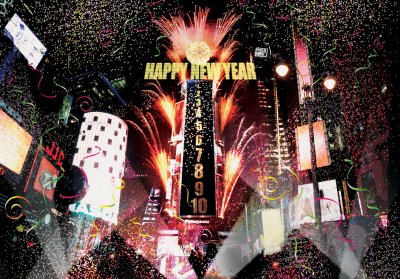

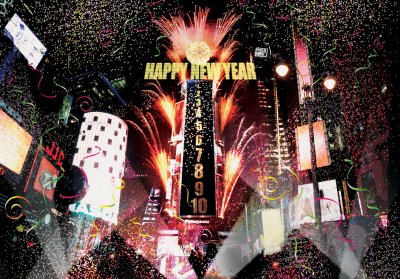

Madison Avenue and Hollywood perpetuates this deceit, glorifying youth and ignoring the aged except for the occasional mirage of a seventy-year-old action hero aided by Botox and stunt doubles. If you need further proof that our culture flees from the truth of Psalm 90:12, just think about what will happen in Times Square tomorrow evening as the clock strikes twelve. Of all the days of the year, New Year’s Eve is the one on which Americans most pointedly acknowledge the passage of time. We have chosen to do so with fireworks and champagne and confetti.

In his wonderful little book Three Philosophies of Life, Christian philosopher Peter Kreeft sums up the message of the Preacher of Ecclesiastes in this way: Everything that we do to fill our days with meaning of our own making boils down to a desperate effort to distract our attention from the emptiness and vanity of life “under the sun.” Our pursuits of pleasure, power, property, importance—they all “come down in the end to a forgetting, a diversion, a cover-up.” Isn’t that what we see in the televised spectacles on New Year’s Eve?

For the Christian, being mindful that we live in time means not running away from the truth that our lives are short, but rather letting it wash over us until we feel the full weight of discontentment that it brings. According to Kreeft, “Our desire for eternity, our divine discontent with time, is hope’s messenger,” a reminder that we were created for more than this time-bound life, fashioned by our timeless God with an eye to a timeless eternity. Being mindful that we live in time should heighten our longing for heaven. In A Severe Mercy, Sheldon Vanauken goes so far as to identify the “timelessness to come” as one of the glories of heaven.

If faithful Christian discipleship requires a mindfulness that we live in time, so does sound historical thinking. To begin with, one of the most important motives for studying the past is the same basic Scriptural truth that inspired the psalmist to ask God to “teach us to number our days.” Put simply, we study the past because life is short.

Although Job’s friends weren’t noted for their wisdom, Job’s friend Bildad the Shuhite conveyed this truth as eloquently as anyone I know of. In perhaps the only useful advice Bildad gave his beleaguered friend, he encouraged Job not to limit his quest for understanding to conversations with the living. “Inquire please of the former age,” Bildad counseled Job, “and consider the things discovered by their fathers, for we were born yesterday, and know nothing” (Job 8:8-9a).

As Bildad understood, with brevity of life comes lack of perspective and narrowness of vision—born yesterday, we know nothing. As Christians, we combat that limitation first of all by searching the scriptures, God’s time-transcending revelation that abides forever. But we also benefit by studying the history that God has sovereignly ordained. At its best, the study of the past helps us to see our own day with new eyes and offers perspectives that transcend the brevity of our own brief sojourn on earth.

In sum, an awareness that we live in time is essential to any meaningful appreciation of history. It is also the foundation of what historians like to call historical consciousness. If there is a single truth that inspires the serious study of history, it is the conviction that we gain great insight into the human condition by situating the lives of men and women in the larger flow of human experience over time. The person who has developed a historical consciousness understands this. He or she would never try to understand individuals from the past while wrenching them from their historical context.

But the person with true historical consciousness doesn’t merely apply this sensitivity to figures from the past. Our lives are just as profoundly influenced by what has gone before us. To quote Christian historian Margaret Bendroth, “People from the past were not the only ones operating within a cultural context–we have one, too. Just like them we cannot imagine life any other way than it is: everyone assumes that ‘what is’ is what was meant to be.” None of us is impervious to the influences of time and place, and being mindful of that is essential to thinking historically.

So where does this leave us? We live in time. Our culture does all that it can to obscure this. The psalmist exhorts us to remember it, and history teaches us that it is true.

May God bless you in 2017.