Today marks the 151st anniversary of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth in Ford’s Theater in Washington, D. C. Since that time more than 16,000 books have been written about Lincoln—one for every three and a half days since his death—and so I’m not going to try to dash out anything new about Lincoln’s role in the preservation of the Union or his proper place in American history more broadly, but I do want to share a thought about how Lincoln’s death was commemorated in the immediate aftermath of the assassination.

I started this blog because I wanted to be in conversation with thinking Christians about what it means to think Christianly about American history. At its best, our engagement with the past should be a precious resource to us, but it can also be a snare, especially because of the temptation that we face to allow our thinking about history to distort our identity as followers of Christ. That temptation, in turn, is but a reflection of a more basic temptation to idolatry that has been a constant theme in the human story. The subtle seduction of idolatry can take innumerable forms, but one of these surely for American Christians over the past two and a half centuries has been the temptation to conflate God’s Church with the American nation.

I’m especially mindful of this today because Lincoln’s assassination instantaneously triggered across the grieving northern states a response that should make us wince, if not shudder. Northerners hardly spoke with one voice, but a common response from northern pulpits was to speak in terms of the president’s “sacrifice” and “martyrdom,” both terms fraught with religious significance. Almost no one missed the symbolism of the timing of Lincoln’s death. Robert E. Lee had surrendered to Ulysses Grant on Palm Sunday—in an event that seemed to signal at long last a northern triumph—and now the nation’s leader was killed on Good Friday. It was child’s play, if childishly foolish, to connect the dots and begin to speak of Lincoln as the nation’s savior and messiah.

Two days later, pastors across the North would mount their pulpits and begin to do so. So, for example, the Reverend Henry Bellows of New York City informed his congregation that “Heaven rejoices this Easter morning in the resurrection of our lost leader . . . dying on the anniversary of our Lord’s great sacrifice, a mighty sacrifice himself for the sins of a whole people.” In Philadelphia, minister Phillips Brooks assured his flock that, “If there were one day on which one could rejoice to echo the martyrdom of Christ, it would be that on which the martyrdom was perfected.”

But not all analogies were between Lincoln and Christ. The day after Lincoln’s death, a Philadelphia newspaper editorialized, “The blood of the martyrs was the seed of the church. So the blood of the noble martyr to the cause of freedom will be the seed to the great blessing of this nation.” Here the central analogy was not between Christ and Lincoln, but between Christ’s church and Lincoln’s nation.

Such conflation of the sacred and the secular continued in the days following, as the nation mourned and the slain president’s funeral procession made its way slowly from Washington, D.C. to Springfield, Illinois. When the procession finally arrived at the grave site in early May, the assembled throng joined their voices in a hymn composed for the occasion:

This consecrated spot shall be

To Freedom ever dear

And Freedom’s son of every race

Shall weep and worship here.

What does it mean to “worship” at the tomb of a departed president?

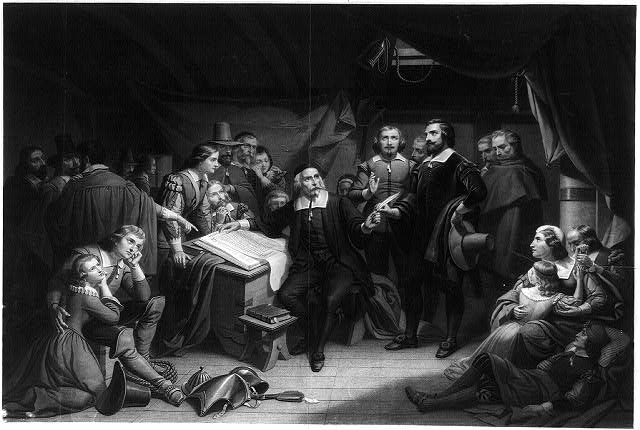

The Christ analogy was also popularized in a series of prints showing what was labeled as the “apotheosis” of Lincoln after his death. One definition of “apotheosis” is “ascension into heaven,” and these prints do regularly show Lincoln being received into the heavenly realm. But another synonym for “apotheosis” is “deification” or “elevation to divine status,” and this definition may apply as well. Significantly, Lincoln is regularly shown being met and embraced by George Washington, who may serve as the gatekeeper into heaven, but might also be effectively a proxy for God the Father. (In the image above, Washington seems to be bestowing on Lincoln a martyr’s crown.) Indeed, banners during Lincoln’s funeral procession were seen to proclaim “Washington the Father, Lincoln the Savior.” Given the common symbolism of Washington as the Founder of the country and Lincoln as its martyred messiah, it’s not much of a stretch to see these images as symbolizing the ascension of the Son (Lincoln) into heaven where he will be seated on the right hand of the Father (Washington).

I admire Abraham Lincoln a great deal, almost as much as any public figure in our nation’s past. But however well intended these images may have been, they can only be described as “patriotic heresy.”