NOTE: This weekend I am away from home on a visit to my father, and I thought I would re-post an older essay while I was away. I composed the reflection below almost exactly a year ago, inspired in part by a powerful chapel message from Wheaton College president Philip Ryken. It remains deeply meaningful to me. I hope you’ll find it of value.–RTM

********

When I began this blog, I promised to deliver essays that explored the intersection of Christian faith, the life of the mind, and the study of the past. This post will seem a little removed from that, but hang in there, and I think you’ll see a connection.

I had heard my younger daughter speak fondly of George Herbert before, but I knew almost nothing about him when I took my seat on the stage at Wheaton’s convocation this past August. “Convocation” is what we call the opening chapel service of the academic year. Wheaton has required chapel services three times a week, but the convocation is considerably more formal than these. The college’s two hundred or so faculty file into the chapel wearing caps and gowns, and it’s a stirring experience. The entire school is gathered under one roof—which I think is neat in and of itself—and the students and faculty sing an opening hymn while the chapel’s massive pipe organ makes the pews vibrate. Sometimes the relentless daily demands of my job cause me to lose sight of the eternal significance of my calling as a teacher. Never during convocation. When the organ is blasting away, and I look out on the student body for the first time since the summer’s hiatus, I regularly feel both delight and fear. I feel anew the wonder that God has called me to labor in this place, and I sense again—as if for the first time—the weight of responsibility that is part of the calling.

As moving as convocation can be, I rarely remember much about the speaker’s message. Perhaps I’m too caught up in my own reverie, or maybe I’m too self-conscious sitting up on the stage in medieval regalia that’s hot and itchy. But this year’s convocation was different. The speaker was Dr. Phillip Ryken, the president of Wheaton College. Dr. Ryken speaks about once a month in chapel during the academic year, and he typically addresses a single over-arching theme from autumn through spring. This year he will be bringing a series of messages on the theme “When Trouble Comes,” and he chose to introduce the series during convocation. (You can download Ryken’s message here.)

It took about ten seconds for him to get my attention.

“It was the spring semester of the academic year, and I was in trouble,” Dr. Ryken began. “Over the course of long weeks that stretched into months, I fell deeper into discouragement, until eventually I wondered whether I had the will to live. I’m talking about me–not somebody else–and I’m talking about last semester.” A hush fell across the chapel. For the next several minutes our president shared briefly about the personal, family, and job-related circumstances that had brought him to a lower point, spiritually and psychologically, than he had ever known.

Discouragement does not begin to convey the state of mind that Dr. Ryken related. Depression comes closer, but I think that despair more truly captures the darkness that enveloped him. My own family has been touched multiple times by something akin to what he was describing. My pulse quickened as Dr. Ryken began to share honestly about his struggles. Then my heart began to ache. Then I began to feel the rush of encouragement that comes when God reminds us that we are not alone.

In describing what his trial felt like, Ryken borrowed two lines from a poem that he had come to identify with. The author was George Herbert. The lines that had literally become Ryken’s testimony were these: “I live to show His power, who once did bring my joys to weep, and now my griefs to sing.”

These words impressed me deeply, and through blurry eyes I scrawled the phrase “griefs to sing” on my program and determined to locate the entire poem as soon as I could. When I got back to my office, a quick Google search took me to Herbert’s poem “Joseph’s Coat,” published in 1633. That same day I entered the entire poem into my commonplace book. I’ve shared it since with several family members and students, and I want to share it with you in a moment.

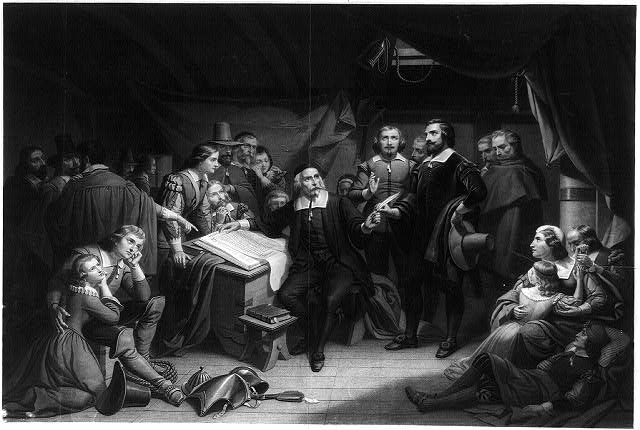

George Herbert (1593-1633) from a 1674 painting by Robert White

But first, a little context. George Herbert (1593-1633) was born into a powerful English family. His father held the aristocratic title “Lord of Cherbury” and sat in Parliament. The son, who was educated at Cambridge and became a favorite of James I, seemed destined to a life of wealth, prestige, and political prominence before he decided to take orders as an Anglican priest in his mid-thirties. For three years he labored as a country parson in a tiny parish southwest of London, before succumbing to tuberculosis at the age of thirty-nine. “Joseph’s Coat” is part of a collection of poems by Herbert that was published shortly after his death.

The poem begins with a set of seemingly contradictory statements:

Wounded I sing, tormented I indite,

Thrown down, I fall into a bed and rest:

Sorrow hath chang’d its note: such is his will,

Who changeth all things, as him pleaseth best.

The image here, as I understand it, is one of opposites. The writer has been dealing with a great trial of some sort, a trial so severe that he speaks of being “wounded,” “tormented,” and “thrown down.” And yet this great pain has been leavened with joy. It is a divine gift, Herbert understands, attributable only to the one who “changeth all things, as him pleaseth best.” It is a joy so powerful and life-giving that Herbert can now sing despite his wounds, compose poetry (this is the meaning of “indite”) amid his torment, and find peace and rest while being thrown down.

Herbert continues, referring to God,

For well he knows, if but one grief and smart

Among my many had his full career,

Sure it would carry with it ev’n my heart,

And both would runne until they found a biere

To fetch the body; both being due to grief.

But he hath spoil’d the race; and given to anguish

One of Joyes coats, ticing it with relief

To linger in me, and together languish.

Herbert reveals that “many” griefs have weighed him down, and he is convinced that if even one of these had been given full sway he could never have survived the assault. (Is there a veiled allusion here to the attraction of suicide?) Undiluted, Herbert’s grief would have been unbearable. Absent the mercy of God, it would have triumphed, prompting body and soul to long for death, literally propelling both to run toward the grave. (A biere was a wooden platform that the dead were placed on before burial.) And yet God in his mercy did intervene. But He hath spoiled the race—this is probably my favorite phrase in the poem. God sends joy as a balm to the writer’s anguish.

I find it significant that Herbert does not write that his anguish disappears. This is about a million miles away from happy-clappy-your-best-life-now theology. The joy that Herbert writes about brings relief and revives hope. But nowhere does Herbert suggest that God has completely eliminated his suffering. In a sense, God has done something more amazing. He has empowered him to live victoriously in the midst of his trial.

Which brings us to Herbert’s concluding declaration:

I live to show his power, who once did bring

My joyes to weep, and now my griefs to sing.

I review these words regularly, and I am praying that Herbert’s declaration will also become the testimony of someone very dear to me. Herbert’s words encourage me greatly, for they testify to “the God who does wonders” (Psalm 77:14). In Life Together, Dietrich Bonhoeffer reminds us that “the Christian needs another Christian who speaks God’s Word to him. He needs him again and again when he becomes uncertain and discouraged.” As followers of Christ, Bonhoeffer writes, we are to “meet one another as bringers of the message of salvation.”

Unfortunately, as Margaret Bendroth notes in her wonderful little book, The Spiritual Discipline of Remembering, most of us live “stranded in the present.” (You can read my review here.) We may refer to the “communion of the saints” when we recite the Apostles’ Creed, but we shut ourselves off almost entirely from the Church across the ages. George Herbert penned “Joseph’s Coat” nearly four centuries ago. I went into a national chain Christian bookstore recently, and apart from a couple of books by C. S. Lewis, I didn’t find a single work more than twenty years old.

Yes, we are stranded in the present, and our lives are poorer for it.

St. Andrew’s Church in Bemerton, Wiltshire, where George Herbert served as rector.