Another year is winding down, and that almost always puts me in a somber mood. Unlike the revelers who’ll be tooting their noisemakers in Times Square three days from now, I have always thought of New Year’s Eve as a time for reflection, a time to evaluate the past twelve months and take stock of the course of my life.

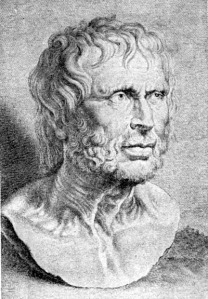

One of my favorite quotations in my commonplace book comes from the ancient Roman author Seneca the Younger (4 B.C. – 65 A.D.). A philosopher, statesman, and playwright, Lucius Annaeus Seneca was one of Rome’s leading intellectuals during the first century after the birth of Christ. He was also as pagan as they come.

I have quoted primarily from Christian writers in sharing passages from my commonplace book, but that’s not because we have nothing to learn from unbelievers. The doctrine of common grace tells us that God causes his rain to fall on the just and the unjust, and thanks to His general revelation we can often glean wisdom even from those who reject wisdom’s Author. I think the quote below is a case in point.

Listen to Seneca’s observation in De Brevitate Vitae—On the Brevity of Life:

The majority of mortals . . . complain bitterly of the spitefulness of Nature, because we are born for a brief span of life, because even this space that has been granted to us rushes by so speedily and so swiftly that all save a very few find life at an end just when they are getting ready to live. . . . It is not that we have a short span of time, but that we waste much of it. But when it is squandered in luxury and carelessness, when it is devoted to no good end, forced at last by the ultimate necessity we perceive that it has passed away before we were aware that it was passing. So it is—the life we receive is not short, but we make it so, nor do we have any lack of it, but we are wasteful of it.

Read woodenly, Seneca seems to be denying one of the most undeniable declarations of Scripture, namely that our lives are short. Time and again, we hear the biblical writers remind us that our lives are no more than a “breath,” a “passing shadow,” a “puff of smoke” (Job 7:7, Psalm 144:4, James 4:14). But far from dismissing this truth, he is calling us to confront a more haunting one: when our lives are at an end, it won’t be the length of our time on earth but the portion of it that we have squandered that grieves us most.

At its best, to quote historian David Harlan, the study of history invites us to join a “conversation with the dead about what we should value and how we should live.” From across the centuries, the pagan Roman admonishes us: “It is not that we have a short span of time, but that we waste much of it. . . . The life we receive is not short, but we make it so.” Not a bad reminder for 2018.