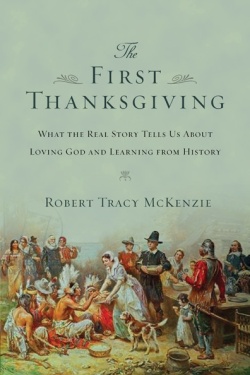

If you’re a long-time reader of this blog, you know that in past years I’ve bombarded readers all November long with essays on the history of Thanksgiving, most of them drawn from my book The First Thanksgiving: What the Real Story Tells Us about Loving God and Learning from History. Because I’ve been taking a “sabbatical” from my blog this year, I’ve spared you that fate this time around, but I find that I can’t bring myself to let the holiday pass without sharing just a few of my favorite Thanksgiving posts.

Anytime I’m interviewed about the history of Thanksgiving, the interviewers always seem to try to direct the conversation to popular myths about the “First Thanksgiving,” with the tiresome result that we end up mostly talking about what the Pilgrims had to eat. For my part, I’d rather discuss the far more important misconceptions most of us have about the Pilgrims: we tend to misunderstand why they came to America in the first place, how they saw themselves, and how they understood the celebration that we–not they–labeled the “First Thanksgiving.” This week I am sharing some past posts that speak to those foundational questions. I hope you enjoy.

**********

Showing Us our Individualism

From where I stand, the most crucial things the Pilgrims have to say to us have nothing to do with Thanksgiving itself. For one thing, the Pilgrim ideal throws into bold relief the supreme individualism of modern American life. The Pilgrims saw the world in terms of groups—family, church, community, nation—and whatever we think of their view, the contrast drives home our own preoccupation with the individual. It was with Americans in mind that French writer Alexis de Tocqueville employed the term later translated as “individualism,” and the exaltation of the self that he observed in American society nearly two centuries ago has only grown relentlessly since.

The individual is now the constituent unit of American society, individual fulfillment holds sway as the highest good, individual conscience reigns as the highest authority. We conceive of adulthood as the absence of all accountability, define liberty as the elimination of all restraint, and measure the worth of social organizations—labor unions, clubs, political parties, even churches—by the degree to which they promote our individual agendas. In sum, as Christian writers Stanley Hauerwas and William Willimon conclude, “our society is a vast supermarket of desire, in which each of us is encouraged to stand alone and go out and get what the world owes us.”

From across the centuries, the Pilgrims remind us that there is another way. They modeled their own ideals imperfectly, to be sure, for as the years passed in New England, they learned from experience what we have known but long ago forgotten, namely, that prosperity has a way of loosening the social ties that adversity forges. By 1644, so many of the original colonists had moved away in search of larger farms that William Bradford likened the dwindling Plymouth church to “an ancient mother grown old and forsaken of her children.”

And yet, in their finest moments, the Pilgrims’ example speaks to us, whispering the possibility that we have taken a wrong turn. Anticipating Hauerwas and Willimon, they observe our righteous-sounding commitment to be “true to ourselves” and pose the discomfiting question: “What if our true selves are made from the materials of our communal life?”

Showing Us our Worldliness

I think that meditating on the Pilgrims’ story might also show us our worldliness. “Do not love the world or the things in the world,” John the Apostle warns, referring to the hollow rewards held out to us by a moral order at enmity with God (I John 2:15). From our privileged perspective the Pilgrims lived in abject poverty, and imagining ourselves in their circumstances may help us to see more clearly, not only the sheer magnitude of pleasure and possessions that we take for granted, but also the power that they hold over our lives.

But for many of us the seductiveness of the world is more subtle than Madison Avenue’s message of hedonism and materialism. God has surrounded us with countless blessings that He wants us to enjoy: loving relationships, rewarding occupations, beautiful surroundings. Yet in our fallenness, we are tempted to convert such foretastes of eternity into ends in themselves, numbing our longing for God and causing us to “rest our hearts in this world,” as C. S. Lewis put it in The Problem of Pain. Here is where the Pilgrims speak to me loudly. It is not their poverty that I find most convicting, but their hope of heaven.

When I was three years old, my proud father, who was superintendent of the Sunday School in our small-town Baptist church, stood me on a chair in front of his Bible class so that I could regale the adults with a gospel hymn. (I know this because my mother was so fond of remembering it.) “When we all get to heaven,” I lisped enthusiastically, “What a day of rejoicing that will be. / When we all see Jesus, / We’ll sing and shout for victory.” On the whole, I don’t think American Christians sing much about heaven any more, much less long for it. I know that I do not, and I don’t think I’m alone.

After decades of talking with Christian young people about the afterlife, Wheaton College professor Wayne Martindale concluded that, “aside from hell, perhaps,” heaven “is the last place we . . . want to go.” This should give us pause, shouldn’t it, especially when we recall how largely heaven figures in New Testament teaching? “Lay up for yourselves treasure in heaven” (Matthew 6:20), Jesus taught His disciples. On the very night He was betrayed He promised His followers that He would prepare a place for them and asked the Father that they might “be with Me where I am” (John 17:24). Paul reminds us of this “hope which is laid up for [us] in heaven” (Colossians 1:5). Peter writes of the “inheritance incorruptible and undefiled” that the Lord “has reserved” for us there (I Peter 1:4).

There are surely many reasons why we find it so hard to “set [our] minds on things above” (Colossians 3:2), including our misperceptions of heaven and our fear of the unknown, but one reason must also be how well off we are in this world. If “churchgoing Americans . . . don’t much want to go to Heaven,” Martindale conjectures, it may be because we feel so “comfortable” on earth. Our creature comforts abound, and for long stretches of time we are able to fool ourselves about the fragility of life. Modern American culture facilitates our self-deception through a conspiracy of silence. We tacitly agree not to discuss death, hiding away the lingering aged and expending our energies in a quest for perpetual youth.

Here the Pilgrims clearly have the advantage on us. In the world as they knew it, material comforts were scarce, daily existence was arduous, starvation was possible, and death was always near. Readily might they echo the apostle Paul: “If in this life only we have hope in Christ, we are of all men the most pitiable” (I Corinthians 15:19). What a consolation to believe that, when their “earthly house” had returned to the dust, they would inherit “a building from God, a house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens” (II Corinthians 5:1). What a help, in time of heartache, to “lift up their eyes to the heavens, their dearest country.” What a balm to their souls, to quote Bradford’s poignant prose, that “they knew they were pilgrims.”

Reminding Us That We are Pilgrims

What difference would it make if such a realization were to penetrate our hearts today? I don’t think it would require that we become “too heavenly minded to be of any earthly good,” as naysayers have sometimes suggested. Asserting that “a continual looking forward to the eternal world” is “one of the things a Christian is meant to do,” C. S. Lewis found in history the pattern that “the Christians who did most for the present world were just those who thought most of the next.” Indeed, in Lewis’s estimation, “It is since Christians have largely ceased to think of the other world that they have become so ineffective in this. Aim at Heaven and you will get earth ‘thrown in,’” he concluded. “Aim at earth and you will get neither.”

Rather than amounting to a form of escapism, “aiming at heaven” might actually enable us to see both ourselves and the world around us more clearly. To begin with, to know we are pilgrims is to understand our identity and, by extension, where our ultimate hope lies. This is something we struggle with, in my opinion.

American Christians over the years have been tempted to confuse patriotism and piety, confounding our national identity as citizens of the United States with our spiritual identity in Christ. We are to “be subject to the governing authorities” (Romans 13:1), Paul enjoins us, and yet never forget that “our citizenship is in heaven” (Philippians 3:19). We should thank God daily for the blessings he has showered on our country, but to know we are pilgrims is to understand that our hope of “survival, success, and salvation” rests solely on our belonging to Christ, not our identity as Americans.

In contradiction to this truth, American culture calls us to be “well-adjusted citizens of the Kingdom of this world,” as Christian philosopher Peter Kreeft trenchantly observes. We who name the “name above all names” have all too often acquiesced, in part by convincing ourselves that, given America’s “Christian culture,” there were no hard choices to be made—that our religious and national identities were mutually reinforcing, if not downright indistinguishable.

But if knowing we are pilgrims means that our true citizenship is in heaven, it also means that we are “strangers” and “aliens” here on earth—yes, even in the United States—and this means, in turn, that we should expect the values of our host country to differ from those of our homeland. American Christians have adopted numerous ploys to obscure this reality, but one of the most influential has been the way we have remembered our past. One example of this is how we have distorted the Pilgrims’ story, clothing them with modern American values and making the future United States—not heaven—their true promised land.