If you’re a long-time reader of this blog, you know that in past years I’ve bombarded readers all November long with essays on the history of Thanksgiving, most of them drawn from my book The First Thanksgiving: What the Real Story Tells Us about Loving God and Learning from History. Because I’ve been taking a “sabbatical” from my blog this year, I’ve spared you that fate this time around, but I find that I can’t bring myself to let the holiday pass without sharing just a few of my favorite Thanksgiving posts.

Anytime I’m interviewed about the history of Thanksgiving, the interviewers always seem to try to direct the conversation to popular myths about the “First Thanksgiving,” with the tiresome result that we end up mostly talking about what the Pilgrims had to eat. For my part, I’d rather discuss the far more important misconceptions most of us have about the Pilgrims: we tend to misunderstand why they came to America in the first place, how they saw themselves, and how they understood the celebration that we–not they–labeled the “First Thanksgiving.” This week I am sharing some past posts that speak to those foundational questions. I hope you enjoy.

**********

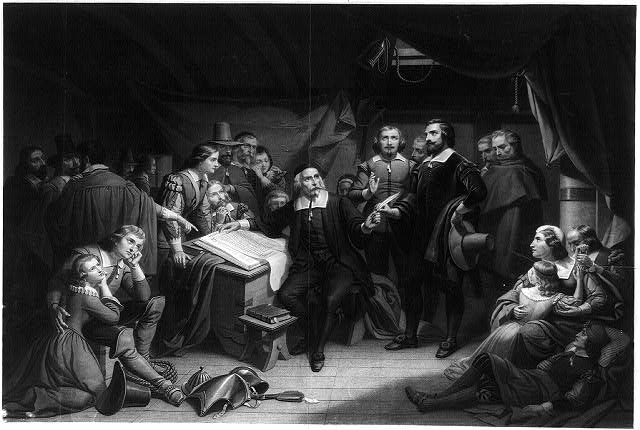

In forty-eight hours families all across America will celebrate Thanksgiving, and some, at least, will link what they are doing to the Pilgrims’ celebration on the coast of Massachusetts in 1621. Although frequently embellished and sometimes caricatured, the story of the Pilgrims’ “First Thanksgiving” is rich with insight and inspiration. The Pilgrims were human, which means that they bore the imprint of the Fall with all its attendant sinful consequences: they were ethnocentric, sometimes judgmental and intolerant, prone to bickering, and tempted by mammon. They were also people of remarkable faith and fortitude—common folk of average abilities and below-average means who risked everything in the interest of their families and their community of faith.

The Pilgrims’ trial began with their voyage on the Mayflower, a 65-day-long ordeal in which 102 men, women, and children crossed the stormy Atlantic in a space the size of a city bus. Following that came a cruel New England winter for which they were ill prepared. (Massachusetts is more than six hundred miles south of London—on a line of latitude even with Madrid, Spain—and the Pilgrims were expecting a much more temperate climate.) Due more to exposure than starvation, their number dwindled rapidly, so that by the onset of spring some fifty-one members of the party had died. A staggering fourteen of the eighteen wives who had set sail on the Mayflower had perished in their new home. Widowers and orphans abounded.

The 1621 Celebration

That the Pilgrims could celebrate at all in this setting was a testimony both to human resilience and to heavenly hope. Yet celebrate they did, most probably sometime in late September or early October after God had granted them a harvest sufficient to see them through the next winter. This is an inspiring story, and it is a good thing for Christians this Thanksgiving to remember it. I don’t know about you, but I am always encouraged when I sit down with Christian friends and hear of how God has sustained them in hard times. Remembering the Pilgrims’ story is a lot like that, although the testimony comes to us not from across the room but from across the centuries.

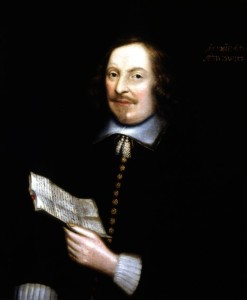

And yet the part of the Pilgrims’ story that modern-day Americans have chosen to emphasize doesn’t seem to have been that significant to the Pilgrims themselves. More importantly, it fails to capture the heart of the Pilgrims’ thinking about God’s provision and our proper response. Most of what we know about the Pilgrims’ experience after leaving Holland comes from two Pilgrim writers—William Bradford, the long-time governor of the Plymouth colony, and Edward Winslow, his close assistant. Bradford never even referred to the Pilgrims’ 1621 celebration (what we call the “First Thanksgiving”) in his famous history of the Pilgrims’ colony, Of Plymouth Plantation. Winslow mentioned it but briefly, devoting five sentences to it in a letter that he wrote to supporters in England. Indeed, the 115 words in those five sentences represent the sum total of all that we know about the occasion!

This means that there is a lot that we would like to know about that event that we will never know. It seems likely (although it must be conjecture) that the Pilgrims thought of their autumn celebration that first fall in Plymouth as something akin to the harvest festivals common at that time in England. What is absolutely certain is that they did not conceive of the celebration as a Thanksgiving holiday.

“Holy Days”

When the Pilgrims spoke of holidays, they used the word literally. A holiday was a “holy day,” a day specially set apart for worship and communion with God. Their reading of the scripture convinced them that God had only established one regular holy day under the new covenant, and that was the Lord’s Day each Sunday. Beyond that, they did believe that the scripture allowed the consecration of occasional Days of Fasting and Humiliation to beseech the Lord for deliverance from a particular trial, as well as occasional Days of Thanksgiving to praise the Lord for his extraordinary provision. Both were comparatively solemn observances, characterized by lengthy religious services full of prayer, praise, instruction, and exhortation.

From the Pilgrims’ perspective, their first formal celebration of a Day of Thanksgiving in Plymouth came nearly two years later, in July 1623. We’re comparatively unfamiliar with it because, frankly, we get bored with the Pilgrims once they’ve carved the first turkey. We condense their story to three key events—the Mayflower Compact, the Landing at Plymouth Rock, and the First Thanksgiving—and quickly lose interest thereafter. In reality, the Pilgrims’ struggle for survival continued at least another two years.

This was partly due to the criminal mismanagement of the London financiers who bankrolled the colony. Only weeks after their 1621 harvest celebration, the Pilgrims were surprised by the arrival of the ship Fortune. The thirty-five new settlers on board would nearly double their depleted ranks. Unfortunately, they arrived with few clothes, no bedding or pots or pans, and “not so much as biscuit cake or any other victuals,” as William Bradford bitterly recalled. Indeed, the London merchants had not even provisioned the ship’s crew with sufficient food for the trip home.

The result was that, rather than having “good plenty” for the winter, the Pilgrims, who had to provide food for the Fortune’s return voyage and feed an additional thirty-five mouths throughout the winter, once again faced the prospect of starvation. Fearing that the newcomers would “bring famine upon us,” the governor immediately reduced the weekly food allowance by half. In the following months hunger “pinch[ed] them sore.” By May they were almost completely out of food. It was no longer the season for waterfowl, and if not for the shellfish in the bay, and the little grain they were able to purchase from passing fishing boats, they very well might have starved.

The harvest of 1622 provided a temporary reprieve from hunger, but it fell far short of their needs for the coming year, and by the spring of 1623 the Pilgrims’ situation was again dire. As Bradford remembered their trial, it was typical for the colonists to go to bed at night not knowing where the next day’s nourishment would come from. For two to three months they had no bread or beer at all and “God fed them” almost wholly “out of the sea.”

Adding to their plight, the heavens closed up around the third week in May, and for nearly two months it rained hardly at all. The ground became parched, the corn began to wither, and hopes for the future began dying as well. When another boatload of settlers arrived that July, they were “much daunted and dismayed” by their first sight of the Plymouth colonists, many of whom were “ragged in apparel and some little better than half naked.” The Pilgrims, for their part, could offer the newcomers nothing more than a piece of fish and a cup of water.

“Oh the Mercy of Our God!”

In the depths of this trial the Pilgrims were sure of this much: it was God who had sent this great drought; it was the Lord who was frustrating their “great hopes of a large crop.” This was not the caprice of “nature,” but the handiwork of the Creator who worked “all things according to the counsel of His will” (Ephesians 1:11). Fearing that He had done this thing for their chastisement, the community agreed to set apart “a solemn day of humiliation, to seek the Lord by humble and fervent prayer, in this great distress.”

As Edward Winslow explained, their hope was that God “would be moved hereby in mercy to look down upon us, and grant the request of our dejected souls. . . . But oh the mercy of our God!” Winslow exulted, “who was as ready to hear, as we to ask.” The colonists awoke on the appointed day to a cloudless sky, but by the end of the prayer service—which lasted eight to nine hours—it had become overcast, and by morning it had begun to rain, as it would continue to do for the next fourteen days. Bradford marveled at the “sweet and gentle showers . . . which did so apparently revive and quicken the decayed corn.” Winslow added, “It was hard to say whether our withered corn or drooping affections were most quickened or revived.”

Overwhelmed by God’s gracious intervention, the Pilgrims immediately called for another providential holiday. “We thought it would be great ingratitude,” Winslow explained, if we should “content ourselves with private thanksgiving for that which by private prayer could not be obtained. And therefore another solemn day was set apart and appointed for that end; wherein we returned glory, honor, and praise, with all thankfulness, to our good God.” This occasion, likely held at the end of July, 1623, perfectly matches the Pilgrims’ definition of a thanksgiving holy day. It was a “solemn” observance, as Winslow noted, called to acknowledge a very specific, extraordinary blessing from the Lord. In sum, it was what the Pilgrims themselves would have viewed as their “First Thanksgiving” in America, and we have all but forgotten it.

As we celebrate Thanksgiving this Thursday, perhaps we might remember both of these occasions. The Pilgrims’ harvest celebration of 1621 is an important reminder to see God’s gracious hand in the bounty of nature. But the Pilgrims’ holiday of 1623—what they would have called “The First Thanksgiving”—more forthrightly challenges us to look for God’s ongoing, supernatural intervention in our lives.

Have a wonderful Thanksgiving.