[This week marks the 153rd anniversary of the three-day-long Battle of Gettysburg, the largest battle of the American Civil War and the largest military engagement ever fought in the western hemisphere. With the anniversary in mind, I am re-posting a series of four essays that I originally penned two years ago after my first visit to the battlefield. The first was a kind of tourist’s report; the remaining three–including the one below–are more properly styled meditations or reflections. My goal in these was to explore what it might mean to remember that bloody conflict through eyes of faith.]

Back to Gettysburg.

Two posts ago I began a series of reflections prompted by my visit to the battlefield there. These meditations are meant as illustrations of what I mean when I suggest that we make our hearts vulnerable as we contemplate the past. So far I’ve shared two examples. The first involved the weight of the past that overcame me at Gettysburg, its palpable reminder of the innumerable host of image-bearers that have gone before us, and the way that this can jolt us out of our own small, comfortable, and self-centered worlds. The second concerned the enormous chasm that separates us from those who clashed on this field a century and a half ago. Realizing this leads us to marvel at the omniscience of God in contrast with how little we actually know of what transpired there.

I’d like to share another meditation. This post will be a bit longer than usual, and I hope you’ll bear with me. The reflection is rooted in the recognition that our inability to recapture what happened on the battlefield isn’t only a reminder of the chasm that separates us from the generations preceding us. It also foreshadows how our own lives will fade from view in generations to come. We all know that life is short, and if we were inclined to think otherwise, the Scripture would insist on bringing us back to reality: “My life is a breath,” sighs Job (Job 7:7). “Our days on earth are a shadow,” his friend Bildad agrees (Job 8:9). Moses observes that our days are numbered (Psalm 90:12), David likens them to a passing shadow (Psalm 144:4), James compares our life’s span to a “puff of smoke” (James 4:14), and Isaiah is reminded of the “flower of the field” that withers away (Isaiah 40:7-8).

Deep down we get this, even as we conspire not to talk about it or acknowledge it. But the wispy, smoke-like, breath-like quality of our lives is not only a matter of length; it is also a matter of legacy. It’s a question of what sort of imprint we will leave behind when we’re gone. The answer, to put it bluntly, is not much of one. It’s not that our lives are without effect. Because we have lived, any number of others lives may be touched. Family members and neighbors, clients and coworkers, patients and students, customers and friends may all be affected, in some cases profoundly so. I’m not discounting that. But once we have passed, the memory of who we are (or were), the knowledge of those inner qualities that define us as unique individuals, will fade quickly into oblivion. How many of us have any more than a faded picture’s acquaintance with our great-grandparents?

The English poet Thomas Gray felt the weight of this. In his famous “Elegy in a Country Church Yard,” the eighteenth-century writer placed his narrator in a cemetery at twilight, where he considers the terse entries on the gravestones and meditates on “the short and simple annals of the poor.” The lives of the “rude forefathers” sleeping there have faded with time, Gray realizes. Humble headstones are all that remain, silent markers that preserve only “their names, their years, spelt by th’unlettered Muse.” It’s not just that our lives are so short, we may read Gray as suggesting. From retrospect they seem so insignificant. We leave but the faintest of footprints for posterity.

Thousands of years before Gray, another writer confronted the same troubling truth. “There is no remembrance of former things,” wrote the Preacher in the Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes. “Nor will there be any remembrance of things that are to come by those who will come after” (Ecclesiastes 1:11). Indeed, the Preacher went on, “there is no more remembrance of the wise than of the fool forever, since all that now is will be forgotten in the days to come” (2:16a). This was one of many reasons convincing the writer that life is empty, meaningless, pointless, absurd. “Vanity of vanities,” he laments in the book’s very first sentence, “all is vanity.”

Through eyes of faith, we read the Preacher’s bitter lament as an example of what Christian philosopher Peter Kreeft calls “black grace,” by which he means God’s revelation to us “by darkness rather than light.” Ecclesiastes hardly captures the true meaning of life. Rather, it brilliantly exposes the futility of life lived “under the sun,” of an existence shorn of all eternal perspective. As we read, we are reminded repeatedly that all of our efforts to deny God and manufacture our own meaning and purpose for life are merely so many acts of self-deception or distraction. Our hope lies not in crafting our own stories, but in realizing that we were born in the middle of a far larger story. The path from despair comes through embracing the One True Story and seeing ourselves rightly as characters in its narrative of hope and redemption.

Intellectually, I understand this, but when I am honest with myself, I realize that the story of the Preacher is often my story, too. I struggle with the desire to manufacture my own meaning, to be the architect of my own immortality. Too often, my drive for accomplishments and reputation are less about a desire to hear “Well done, good and faithful servant” in eternity, and more about erecting monuments to myself in this present age.

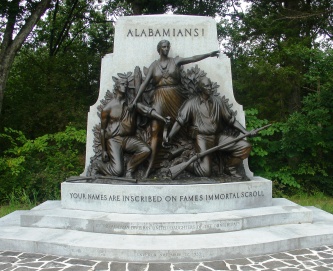

Here, too, Gettysburg speaks to me. Visitors to Gettysburg not only get a glimpse into the battle that raged there in 1863. They also see evidence of how those who survived the battle wished to be remembered. The ten square miles of Gettysburg National Military Park constitute the largest statuary garden in the world. There are monuments and markers galore (somewhere in the neighborhood of fourteen hundred all told), the vast majority erected in the late-19th and early-20th centuries as the survivors of the battle were entering old age.

Monument to the 140th New York Infantry on Little Round Top

It would be interesting to undertake a systematic study of the inscriptions on these monuments. I did not, but I did stop to read a fair number as I walked the battlefield. One of the things that struck me is how mundane their perspective generally is. The vast majority simply repeat the same kind of details that would go into an action report after battle. A typical monument explains that the military unit being commemorated was positioned at such and such a spot for such and such a purpose, with such and such a result. An enumeration of casualties invariably follows, and sometimes the names of those killed.

Attempts to speak to the motivation or values of those involved are in fact extremely rare. They usually involve brief references to “duty,” “valor,” or patriotism. None of these is intrinsically Christian, of course, and a pagan soldier in ancient Rome would have welcomed them on a monument to Caesar’s legions.

What seems lacking in these monuments is any effort to connect what happened at Gettysburg to some larger narrative that would give the battle transcendent meaning. Such a narrative had been provided years earlier, however, in the most famous effort to commemorate those who fought there, although this commemoration was not a monument, but a speech.

We rightly remember the Gettysburg Address for its eloquence, but how deeply do we think about it? I may offend some in saying this, but to think Christianly about it is to see it as deeply flawed. Like the Preacher’s contemplation of life “under the sun,” its perspective is relentlessly earthbound, and at least one of its claims is vaguely blasphemous.

Probably the Address’s best known passage is its opening sentence: “Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation: conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” We live in a talk-show culture in which contemporary political rhetoric is relentlessly parsed and dissected and critiqued unmercifully, but let a few generations pass and chisel the rhetoric in granite on the mall in Washington, and it becomes sacrosanct in our eyes. It might free us up to re-examine the Address afresh if we remember that it was roundly denounced when it was delivered.

Lincoln and Gettysburg Address

As in our own day, much of the criticism was politically motivated. We forget that, like so many other politicians before and since, Lincoln used a public appearance before a large crowd as an opportunity to make a political statement. In November, 1863, the North was badly divided over the president’s recent Emancipation Proclamation. The Republican Party supported it, while the Democratic Party unanimously denounced it. And so the Republican leader wasted no time in defending his administration when he helped to dedicate the new military cemetery in Gettysburg, even though he never once referred to emancipation explicitly.

His argument was essentially historical. At worst misleading, at best debatable, it rested on a highly selective reading of the country’s founding. For years Lincoln had been insisting that his desire to end slavery was in keeping with the original vision of the Founding Fathers. “The fathers of the government expected and intended the institution of slavery to come to an end,” he proclaimed repeatedly during the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858. In advocating the restriction of slavery and its ultimate demise, Lincoln informed the audience that “I have proposed nothing more than a return to the policy of the fathers.” Lincoln’s view was a libel on the Founders, Democrat Douglas rejoined. Offering his own reading of American history, Douglas informed cheering Democrats that “our fathers made this government divided into Free and Slave States, recognizing the right of each to decide all its local questions for itself.”

And so when Lincoln began by telling the assembled throng at Gettysburg that our fathers had been “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” the politically savvy among them immediately recognized a familiar refrain in a long-standing partisan debate. And when, a couple of minutes later, Lincoln concluded his brief remarks by implying that the Union dead at Gettysburg had died so that the nation might have “a new birth of freedom,” the crowd understood that he was enlisting the fallen at Gettysburg in the controversial cause of emancipation.

Republicans saw nothing exceptional in this. Democrats were livid. It was to uphold the Constitution, the Chicago Times assured its readers, “and the Union created by it, that our officers and soldiers gave their lives at Gettysburg.” What the president had done at Gettysburg was simply despicable. “How dare he,” thundered the Times editor, “standing on their graves, misstate the cause for which they died, and libel the statesmen who founded the government? They were men possessing too much self-respect to declare that negroes were their equals, or were entitled to equal privileges.”

As a historian, I see northern Democrats’ response to the Address as understandable (although their reading of history was just as one-sided as Lincoln’s). As a Christian historian, I am more disappointed by the way that Republican evangelicals across the North embraced Lincoln’s speech, for it contained elements that they should have found troubling.

For one thing, the Address is a classic example of rhetoric that conflates sacred and secular. Read broadly, Lincoln’s address was a masterful effort to situate the tragedy of the American Civil War in a larger story of redemption. The thing being redeemed, however, is not God’s Church but the United States. The author of redemption is not the Lord but “the people.”

The story Lincoln tells begins with its own creation account. “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth,” the opening verse of Genesis declares. In the beginning “our fathers brought forth” the United States, Lincoln proclaims. Their values now bind us. Their vision–as interpreted by Lincoln–obliges us. Ever since Lincoln’s death there have been countless efforts to “baptize him posthumously,” as Christian scholar Allen Guelzo notes in his marvelous biography, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President. Guezlo argues persuasively, however, that although Lincoln was biblically literate and far from an atheist, he nevertheless died unconvinced of the gospel. What is more, although he employed biblical rhetoric and adopted biblical cadences in his speeches, he rarely if ever referred to the Bible as authoritative. As late as 1863, at least, the bedrock of his argument against slavery was not scripture but the Declaration of Independence and its assertion–penned by an apostle of the Enlightenment who owned 150 slaves–that “all men are created equal.”

Lincoln goes on to make two other assertions that ought to have troubled the thinking Christians in his audience. The first is his statement that “the brave men who struggled” at Gettysburg–presumably he meant the Union men–had “consecrated” the ground. To consecrate is to “set apart as sacred to God.” Something that has been consecrated is now “holy.” When the great “I AM” spoke to Moses from the burning bush, He informed the trembling herdsman that he was standing on holy ground. Lincoln told his audience the same thing. In what possible sense could that be true? It makes little difference whether you believe that Lincoln was speaking literally or figuratively. In his choice of words the president was draping the state with religious imagery and eternal significance, and that, however well-intended, is a form of what Christian scholar Steven Woodworth aptly labels “patriotic heresy.”

Second, Lincoln suggested that the blood of the Union dead justified the Union cause. He urged his audience to renew their commitment to the struggle precisely because others had given “the last full measure of devotion” on its behalf. My grandfather served in WWI, my father in WWII, and my son is currently in the Marine Corps, so I want to be very careful in choosing my words here. We can rightly respect, admire, and appreciate those who, through suffering and great danger have risked their lives in our defense. But that is a different thing from maintaining that the spilling of blood necessarily ennobles the cause for which it is shed.

We would not accept that view with regard to the storm troopers who died in the service of Adolph Hitler, nor the Islamic terrorists who knowingly went to their deaths on 9/11. And as American Christians we ought not to swallow the argument as applied to our own soldiers. If we accept the view that death in war automatically justifies the perpetuation of that war–so that the “dead shall not have died in vain,” as Lincoln put it–we abdicate our calling to live as salt and light. When we do so, the church forfeits its prophetic voice and becomes merely an extension of the state.

Thinking Christianly about the past requires that we make our own hearts vulnerable, so my purpose in sharing these thoughts is not so that we can smugly condemn those who have gone before us. Instead, we are called to identify with them. Their example reminds us, warns us, of the ever present temptation to confuse our identity as Christians with other loyalties and attachments, whether nation, race, class, or party. This is but one manifestation of the more general seduction that the Preacher of Ecclesiastes knew well: the illusion that we make our own meaning in life, satisfying our souls on our own terms, in our own way. Others have unknowingly succumbed. Why should we be immune?

Search our hearts, O Lord . . .