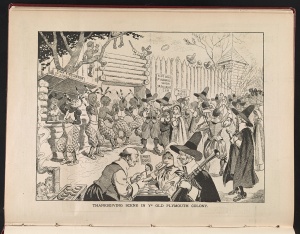

On the whole, the Pilgrims haven’t fared well in modern-day popular memory. We tend to caricature them—clothing them in buckles and black hats and arming them with blunderbusses. We sometimes condemn them—casting them as religious fanatics intolerant of difference and suspicious of anything fun. What we seldom do is consider them carefully, opening ourselves to the possibility that they might have something to teach us. I wrote The First Thanksgiving not because I’m a Pilgrim groupie, but because I was convinced that when we take their story seriously we can learn a lot about ourselves—about what we love, how we see the world, and how we live within it.

Unfortunately, when amateur historians have taken the Pilgrims seriously they have typically produced what Christian historian Mark Noll calls “ideological history.” Ideological history succumbs to the temptation to go to the past for ammunition instead of illumination—to “prove points” instead of to gain understanding. We fall into this trap whenever we know too definitely what we want to find in the past, when we can already envision how our anticipated “discoveries” will reinforce values that we already hold or promote agendas to which we are already committed. Rush Limbaugh’s Rush Revere and the Brave Pilgrims is a textbook example of this kind of history. (I’ve written on it most recently here and here.) If you buy this book you won’t learn much about the Pilgrims’ worldview, but you will learn a great deal about Rush Limbaugh’s.

You don’t have to be a liberal academic or a partisan talk-show host to fashion ideological history, however. Well-meaning Christians do so all the time as well. When it comes to our treatment of the Pilgrims, a classic case in point would be Kirk Cameron’s 2012 feature-length documentary, Monumental. I want to say up front that I have nothing personal against Kirk Cameron. Many of the critical reviews of Monumental on the internet ooze condescension and contempt; they seem to flow from a starting point that takes for granted the absurdity of an evangelical perspective on anything. That is not where I am coming from, and I hope that is obvious. I want to stand with Kirk Cameron in his apparent desire to honor God and train his children in biblical wisdom. But I must stand against his approach to American history, which is both historically inaccurate and theologically confused. In this post and the next two, I want to explain what I mean.

Although I am sure Cameron’s intentions are honorable, Monumental exhibits all the marks of ideological history. The documentary is not interested in understanding the complexity of the Pilgrims’ values and beliefs. Cameron and co-producer Marshall Foster are on a quest for ammunition more than enlightenment. Committed to a particular set of values, they want to use the Pilgrims to make a historical argument for their contemporary agenda. In their hands, the Pilgrims become two-dimensional props for an extended infomercial.

A case in point would be the central premise on which the documentary is grounded. According to Cameron, the documentary “seeks to discover America’s true ‘national treasure’— the people, places, and principles that made America the freest, most prosperous and generous nation the world has ever known.” His search leads him to the Pilgrims. “There’s no question,” Cameron explains, that “the tiny band of religious outcasts who founded this country hit upon a formula for success that went way beyond what they could have imagined. How else can you explain the fact that they established a nation that has become the best example of civil, economic and religious liberty the world has ever known?”

So the Pilgrims “founded this country”? They “established” this nation? Really? I will pass over the utter illogic of such a statement to focus on a more important point: The Pilgrims weren’t remotely thinking about founding a country, nor would they want to be remembered for doing so. They were English to the core and came to North America, in part, to try to preserve aspects of their English identity. As Pilgrim Edward Winslow later recalled, they feared “how like we were to lose our language and our name of English” if they remained in Holland.

But more important than their English identity was their identity in Christ, which was paramount in their thinking. Arguably the most important aspect of the Pilgrim’s worldview is also the easiest for us to overlook, precisely because it seems so very familiar to us. Here it is: the Pilgrims thought of themselves as “pilgrims.” Monumental misses this completely.

Here is what I mean. The powerful message originally contained in the word pilgrim is now mostly lost on us. We speak of “the Pilgrims” without thinking about the term, using it as a kind of shorthand title for the group that came over on the Mayflower and played a role in the founding of America. Literally, the word “pilgrim” refers to a person on a journey, often, but not always, to a place of particular religious significance. When Americans first began to speak of “the Pilgrims” in the 1790s this meaning was still understood, but even then it was common to mistake the group’s destination. In annual commemorations of the (supposed) landing at Plymouth Rock (a landmark the Pilgrims themselves never mentioned), orators repeatedly described the Pilgrims as religiously motivated but worldly focused.

In 1820, for example, Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster figuratively positioned the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock and invited his audience to listen in as their ancestors contemplated the future of the land to which God had brought them. “We shall plant here a new society,” the senator imagined the Pilgrims saying to one another. “We shall here begin a work that shall last for ages” they vowed, as they peered into the future and saw the fulfillment of their vision in a new country built upon Pilgrim principles.

Toward the close of the nineteenth century, a popular magazine employed a similar rhetorical convention to make the same point. This time it was the Pilgrims’ elder William Brewster who stood alone on the rock and supposedly prophesied:

Blessed will it be for us, blessed for this land, for this vast continent! Nay, from generation to generation will the blessing descend. Generations to come shall look back to this hour . . . and say: “Here was our beginning as a people. These were our fathers. Through their trials we inherit our blessings. Their faith is our faith; their hope is our hope; their God our God.”

Countless politicians, preachers, and writers echoed the point: The tiny Pilgrim band had forged the “nucleus of a mighty civilization.” They “were among the main foundation-layers of our Great Republic.” They brought with them “the germ of our national life.”

Monumental perpetuates this view. As told by Cameron and Foster, the Pilgrims’ journey ended when they reached the shores of America. The future United States was their Canaan, their promised land. It can be inspiring to remember their story that way. According to both Governor William Bradford and Deacon Robert Cushman, however, that’s not how the Pilgrims themselves saw it. Certainly, they were searching for an earthly location where they could perpetuate proper worship and earn a better living, but to the degree that the Pilgrims thought of themselves as “pilgrims,” they meant that they were temporary travelers in a world that was not their home.

This is clear from the context in which Bradford famously used the term in his history Of Plymouth Plantation. Toward the middle of book I, Bradford movingly described the Pilgrims’ departure from Holland, as the members of the Leiden congregation who were leaving for America said goodbye to the friends and loved ones remaining behind. (Bradford himself was leaving his three-year-old son.) With “an abundance of tears,” Bradford recalled, the group left “that goodly and pleasant city which had been their resting place near twelve years; but they knew they were pilgrims, and looked not much on those things, but lift up their eyes to the heavens, their dearest country, and quieted their spirits.”

As he penned these words, Bradford was almost certainly thinking of the eleventh chapter of the book of Hebrews, that great survey of Old Testament heroes of the faith. There, in the text of the 1596 edition Geneva Bible that Bradford brought with him to Plymouth, we read that these men and women “confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on earth.” The writer goes on to explain that any “that say such things [i.e., think of themselves as pilgrims], declare plainly, that they seek a country,” but the country sought is a “heavenly” one (Hebrews 11:13-16).

In a much less known passage actually written earlier, Deacon Cushman employed similar imagery. In an essay published in 1622, Cushman reviewed the argument for “removing out of England into the parts of America.” In the introduction, Cushman emphasized that God no longer gave particular lands to any people, as he once had given Canaan to the nation of Israel. “But now we are all in all places strangers and pilgrims, travelers and sojourners,” Cushman observed, “having no dwelling but in this earthen tabernacle.” Perhaps with II Corinthians 5:1 in mind, the deacon elaborated, “Our dwelling is but a wandering, and our abiding but as a fleeting, and in a word our home is nowhere, but in the heavens, in that house not made with hands, whose maker and builder is God, and to which all ascend that love the coming of our Lord Jesus.”

Potentially, we can remember the Pilgrims as our spiritual ancestors and still preserve their understanding of “pilgrimage.” When we remember them as our national ancestors, however—as key figures in the founding of America—we unwittingly refashion that sense of pilgrimage into something they wouldn’t recognize. Monumental does this repeatedly.