As I was backing out of the driveway this morning, I was distressed to see a “For Sale” sign in the front yard of our very dear next-door neighbors. I backed down the street to where I could see the sign more clearly and discovered, to my relief, that it read as follows: “FOR SALE BY OWNER,” and then in much smaller, handwritten print, “One Day Only: April 1st, 2015.”

April Fools’ Day. I’ve hated this day all of my life.

At any rate, the prank got me to thinking about April Fools’ Days in American History, and my thoughts went to one of the most ominous April 1sts in our past. It was April 1st, 1861, and the United States was perched precariously on a precipice. (How’s that for alliteration?) Since the election of Abraham Lincoln as president the preceding November, seven southern states had issued resolutions purporting to sever their ties with the Union. A half dozen more were sorely tempted to follow suit, and would very likely do so if the Federal government took steps to restore the Union by force. As the country waited for the inauguration in March of its new Republican president, the seceding states took steps to constitute themselves the Confederate States of America and set to work confiscating all federal property—forts, arsenals, customs houses, and mints—within their borders. By the time Lincoln took the oath of office on March 4th, 1861, the Union was visibly collapsing and the authority and prestige of the U. S. government was at its nadir.

Lincoln and his cabinet—which included four of his rivals for the Republican presidential nomination—were deeply divided as to how to respond to the crisis. In his inaugural address, the president had tried to show both moderation and resolve. On the one hand, he had gone out of his way to try to reassure his southern critics that they need not fear a Republican presidency. On the other, he had insisted that “secession is the very essence of anarchy” and declared that the Union is “perpetual.” Drawing a line in the sand, he had pledged (somewhat redundantly) to “hold occupy, and possess” all federal property within the rebellious states. Implicitly, this seemed to obligate the new president, at the very least, to do all within his power to maintain control of the federal forts in the lower South not yet in Confederate hands—most notably Fort Sumter in the mouth of Charleston harbor.

Lincoln and his cabinet—which included four of his rivals for the Republican presidential nomination—were deeply divided as to how to respond to the crisis. In his inaugural address, the president had tried to show both moderation and resolve. On the one hand, he had gone out of his way to try to reassure his southern critics that they need not fear a Republican presidency. On the other, he had insisted that “secession is the very essence of anarchy” and declared that the Union is “perpetual.” Drawing a line in the sand, he had pledged (somewhat redundantly) to “hold occupy, and possess” all federal property within the rebellious states. Implicitly, this seemed to obligate the new president, at the very least, to do all within his power to maintain control of the federal forts in the lower South not yet in Confederate hands—most notably Fort Sumter in the mouth of Charleston harbor.

The ranking member of Lincoln’s cabinet—Secretary of State William Seward—led a faction within the administration that sought to avoid a showdown if possible. Seward had much more experience in national politics than Lincoln and had been the odds-on favorite for the Republican presidential nomination in 1860, before losing out to Lincoln on the 3rd ballot. It is quite possible that he had accepted the State Department post—historically the most prestigious and influential cabinet appointment—with the intention of serving as the de facto head of the administration, pulling the strings behind the scenes while the inexperienced Lincoln played the role of puppet and figurehead. Toward the end of March, Seward had met secretly with representatives of the Confederate government, assuring them that the government would not use force to uphold its authority and promising—without Lincoln’s knowledge or approval—that the Union troops assigned to Fort Sumter would soon evacuate the installation.

As March drew to a close, and as it became increasingly evident to Seward that Lincoln intended to uphold his inaugural pledge, the secretary drew up one of the most remarkable memoranda ever given to a sitting president by a high-ranking government official. Because Seward forwarded the memorandum—titled “Some Thoughts for the President’s Consideration”—on April 1st, historians have commonly referred to the document as Seward’s “April Fools’ Memorandum.” In truth, the proposals it contains are so outlandish that it is tempting to conclude that the secretary was pranking the president, but he wasn’t. He was in dead earnest.

After criticizing Lincoln for having failed to define a clear policy, “either foreign or domestic,” Seward went on to repeat his recommendation that Sumter be evacuated. In Seward’s mind, this sort of concession to the South was the best way both to keep the upper South in the Union and avoid the tragedy of civil war.

Then came the clincher. Under the heading “For Foreign Nations,” the Secretary of State recommended to the president that the administration “demand explanation from Spain and France, categorically, at once.” Spain had recently sent troops into Santo Domingo, while France was casting its eyes on Mexico, and Seward was proposing to challenge both on the grounds that they were in violation of the Monroe Doctrine. “If satisfactory explanations are not received from Spain and France,” Seward went on, the president should “convene Congress and declare war against them.” Although he didn’t spell out his rationale for the president, Seward clearly believed that the best way to unify the country was to provoke a war with one of the major powers of Europe.

But what if Lincoln was not prepared to take the lead on such a drastic policy? The Secretary of State concluded his memorandum with the following presumption:

Whatever policy we adopt, there must be an energetic prosecution of it. For this purpose, it must be somebody’s business to pursue and direct it incessantly. Either the President must do it himself and be all the while active in it, or devolve it on some member of his Cabinet. Once adopted, debates on it must end, and all agree and abide. It is not in my especial province but I neither seek to evade nor assume responsibility.

Lincoln replied in writing to Seward the same day, although it is not clear whether his brief note was ever actually delivered. What is clear is that Lincoln ignored Seward’s proposal of provoking a European war. He also effectively declined the Secretary of State’s polite offer to take over the management of his administration. If something “must be done,” the president wrote in his reply, I must do it.”

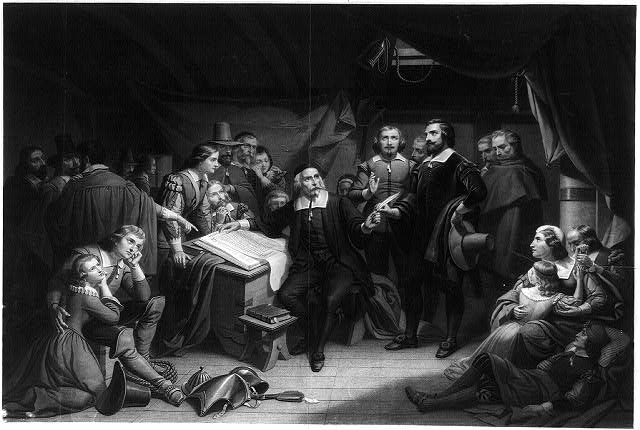

This period of time after Lincoln’s inauguration while fighting had not yet commenced must have been a fascinating one for all involved. Momentous decisions needed to be made and I can just see members of Lincoln’s cabinet such as Seward huddling together and planning to make those decisions, completely discounting Lincoln himself. They had such egos and were so sure that Lincoln could be shunted aside as a figurehead. But how really amateurish Seward really was! I love how Lincoln let these men plot and plan and then he simply did what he believed was best completely ignoring their machinations. I wonder when Seward and others actually realized what they were up against?