Last weekend I posted two essays in a four-part series on how American memory of the First Thanksgiving has changed over the past four centuries. And it definitely has changed, and changed dramatically. As I explained last weekend, for most of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, Americans mostly either were ignorant of the Pilgrims’ 1621 celebration or unimpressed by it. This weekend my goal is to explain why Americans finally embraced the story of the First Thanksgiving in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century.

**********

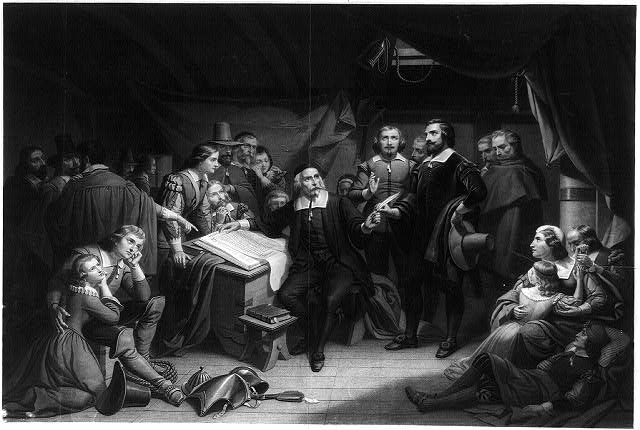

It is no coincidence that Jennie Brownscombe’s famous painting of the First Thanksgiving dates from the 20th century, not earlier.

In my last post on the First Thanksgiving in American Memory, I called attention to a number of trends in the latter half of the nineteenth century that opened the door for Americans gradually to embrace the Pilgrims as ancestors critical to the American founding. There was one other, absolutely crucial trend at the close of the century that made the adoption of the Pilgrims as honorary Founders not only possible but desirable. That trend was immigration.

By the 1890s, the most pressing political challenge facing the country was no longer the preservation of sectional harmony or conflict with Native Americans, but rather how to assimilate an unprecedented influx of new immigrants to the United States. From the 1880s into the early 1920s, immigrants from southern and eastern Europe—Poles, Italians, Russians, Greeks, Czechs, Armenians, Croats, and Ruthenians, among others—would flood into the United States by the millions, creating anxiety among the native born that their country was being overrun by inassimilable aliens.

As human beings we always remember the past from the vantage point of the present, and in the late-nineteenth century native-born Americans increasingly surveyed the country’s history in the light of contemporary concerns about immigration. The effect on popular memory of the Pilgrims was dramatic. In 1841 Americans had recalled the Pilgrims primarily as New Englanders, or as Puritans, or as generic whites striving to coexist with Indians. By the dawn of the twentieth century they remembered them first and foremost as immigrants. More precisely, by 1900 they had transformed the Pilgrims into America’s model immigrants, the standard against which all newcomers should be measured.

Critics of the new immigrants compared them to the Pilgrims and found them wanting. Noting that Thanksgiving was “the nation’s tribute” to the “sublime strength of character which ennobled the Pilgrims,” a Christian magazine based in Chicago editorialized that the influx from southern and eastern Europe was bringing with it “the germs of a moral malaria.”

The department store Marshall Field and Company echoed this concern in a full-page Thanksgiving ad in 1920. The advertisement featured in the foreground a large, stereotypical Pilgrim male standing on Plymouth Rock, and in the background a sea of immigrants entering the country through Ellis Island. “What metal do they bring to this melting pot?” the ad inquired. “Do they bear the precious ore of the early Pilgrims, or the dross of the disturber? . . . We want only those who—like the Pilgrims of old—landed here with gratitude on their lips and thanksgiving in their hearts.” The image from Life magazine below presented much the same visual message–absent the leading rhetorical question–as early as 1887.

The more optimistic believed that the example of the Pilgrims could be used to “Americanize” immigrants. The Citizenship Committee of the American Bar Association found in the history of Thanksgiving an ideal context for inculcating “the principles and ideals of our government in the minds and hearts of the people.” Progressive educators agreed. Soon Thanksgiving materials proliferated in teachers’ magazines and published curricula, and by the 1920s a survey of elementary school principals revealed that Thanksgiving was the single most celebrated holiday.

School history textbooks, which had rarely referred to the Pilgrims prior to 1900, soon devoted whole chapters to the voyage of the Mayflower and the First Thanksgiving. “Boys and girls are especially interested in the Plymouth colony,” noted the author of A History of Our Country, for Higher Grades. “It is the only one of all the American colonies that has given to the United States a holiday,” an observance which “makes Americans a more thankful race.”

By emphasizing the Pilgrims’ perseverance in adversity, the new curriculum both challenged and gave hope to new immigrants. A young Russian immigrant at the turn of the century, for example, learned from her history text that

America started with a band of Courageous Pilgrims [who had] left their native country as I had left mine. . . I saw that it was the glory of America that it was not yet finished. And I, the last comer, had her share to give, small or great, to the making of America, like those Pilgrims, who came in the Mayflower.

Like this young immigrant, for most of the last century Americans learned in grade school that “America started” with the Pilgrims. Although they rarely studied the First Thanksgiving after grade school, this early exposure was enough to make the Pilgrim story a central chapter in Americans’ collective historical memory.

Once the Pilgrims had became honorary Founding Fathers, Americans rushed to enlist them as allies in the political struggle du jour. In the midst of the Progressive Era, Theodore Roosevelt placed the Pilgrims on the side of the regulation of Big Business, observing that “the spirit of the Puritan was a spirit which never shrank from regulation of conduct if such regulation was necessary for the public weal.” During the height of the McCarthy Era, the International Nickel Company took out an ad in the Saturday Evening Post portraying the Pilgrims as both libertarian and anti-Communist; in 1623 the Pilgrims had “turned away from governmental dictation” because they realized that “there was plenty for ALL, only when men were Free to work for themselves.” At the close of the turbulent 1960s, Look magazine recalled the Pilgrims as “dissidents” and “commune-builders.”

During World War Two the Pilgrims became ideal soldiers. In its 1942 Thanksgiving issue, Life reminded readers that the Pilgrims had been a “hardy lot,” a “strong-minded people” who “waged hard, offensive wars” and never forgot that “victory comes from God.” When President Roosevelt declared after Pearl Harbor that the nation’s cause was “liberty under God,” the magazine concluded that he might as well “have been speaking for the Puritan Fathers.” At the height of the Cold War, the Chicago Tribune remembered the First Thanksgiving as “our first détente,” but the paper also enlisted the Pilgrims on the side of military preparedness; their security had been rooted in “the clear demonstration that they had the equipment and the will to fight for their survival.”

But not only for their survival, for the Pilgrims had believed in “the restless search for a better world for all,” as President Lyndon Johnson observed in 1965 as he appealed to “the principles that the early Pilgrims forged” to explain why U. S. sons were fighting in Viet Nam. Yet the Pilgrims had also cherished peace, for as Bill Clinton told the nation a generation later, the same spirit that prompted them to sit down with the Wampanoag had also infused efforts for a “comprehensive peace in the Middle East.”

Our adopted Founders have been remarkably malleable, wouldn’t you say?

Pingback: Thanksgiving – The Personal Pretensions of a Catholic Hamilton