TWENTY-ONE days to Thanksgiving and counting. As an alternative to the ubiquitous countdown to Black Friday, each weekday between now and Thanksgiving I will be posting brief essays on the history of the First Thanksgiving and its place in American memory. The essay below ruminates on the Great Thanksgiving Hoax, a spurious Thanksgiving proclamation attributed to Pilgrim Governor William Bradford that has been making the rounds for decades.

**********

History is not the past itself, but only that tiny portion of the past that human beings remember. I’ve shared in a previous post the memorable word picture that C. S. Lewis has given us to illustrate that distinction. In his essay “Historicism,” Lewis concluded that even a single moment involves more than we could ever document, much less comprehend. He then went on to define the past in this way:

The past . . . in its reality, was a roaring cataract of billions upon billions of such moments: any one of them too complex to grasp in its entirety, and the aggregate beyond all imagination. By far the greater part of this teeming reality escaped human consciousness almost as soon as it occurred. . . . At every tick of the clock, in every inhabited part of the world, an unimaginable richness and variety of “history” falls off the world into total oblivion.

“The secret things belong to the Lord our God,” Deuteronomy 29:29 tells us. Only “those things which are revealed belong to us.” If the past is a domain that God has created, then Lewis’s metaphor drives home a discomfiting truth: The Lord has chosen to keep most of the past hidden from us.

This is not a limitation we are disposed to accept. We chafe against it, and when it suits our purposes, we fill in the gaps in God’s revelation with a “past” of our own imagining. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong about imagining what the past might have been like, of course. The problem comes when we mistake this imagined past for reality. To say that this happens all the time would be an understatement. Typically, only a portion of popular memory of the past is firmly grounded in historical evidence. The other part—often the more entertaining part—consists of stuff somebody made up.

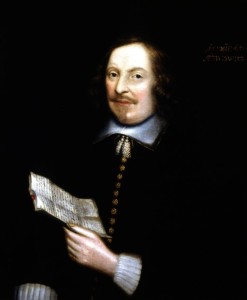

Americans have long struggled with the temptation to make up stuff about the First Thanksgiving. That is because we have loaded with great significance an event about which almost no firsthand evidence survives. The only surviving firsthand account of a celebration in Plymouth in 1621 comes from the pen of Pilgrim Edward Winslow, an assistant to the Plymouth Colony’s governor, William Bradford. Upon the arrival of a ship from England in November 1621, Winslow crafted a cover letter to accompany reports to be sent back to the London merchants who were financing the Pilgrims’ venture. In his letter—the main purpose of which was to convince the investors that they weren’t throwing their money away—Winslow described the houses the Pilgrims had built, listed the crops they had planted, and emphasized the success they had been blessed with. To underscore the latter, he added five sentences describing the abundance they now enjoyed.

Our harvest being gotten in, our Governor sent four men on fowling; that so we might, after a more special manner, rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labours. They four, in one day, killed as much fowl as, with a little help besides, served the Company almost a week. At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our Arms; many of the Indians coming amongst us. And amongst the rest, their greatest King, Massasoyt, with some ninety men; whom, for three days, we entertained and feasted. And they went out, and killed five deer: which they brought to the Plantation; and bestowed on our Governor, and upon the Captain, and others.

These 115 words constitute the sum total of contemporary evidence regarding the First Thanksgiving. They’re evocative, but they’re also vague, and if we wanted to, we could compile a whole list of details commonly taken for granted about the occasion which we could never prove from Winslow’s brief description. Why are we so sure that turkey was on the menu? Why do we assume that the feast took place in November? Why do we take for granted that the Indians were invited (instead of just crashing the party)? Can we positively conclude that there was a religious dimension to the celebration? Can we positively conclude that there was not?

There are a lot of gaps here that we’d like to have filled in. In the words of the late radio and television commentator Paul Harvey, we want to know “the rest of the story.”

In my next post, I want to introduce you to a novelist that so successfully filled in the gaps that her fictional recreation of the First Thanksgiving soon became historical reality for a whole generation of Americans. Before doing so, I want to point you briefly to a hoax that continues to mislead many of us who long for the rest of the story.

I first encountered William Bradford’s supposed First Thanksgiving Proclamation when my family and I enjoyed Thanksgiving dinner at the home of some dear friends from our church. Knowing that I was a historian, the host pulled me aside before the meal to tell me that he had found the text of Governor Bradford’s proclamation calling for the First Thanksgiving, and that he planned to read it before asking the blessing. Here is what he had found:

Inasmuch as the great Father has given us this year an abundant harvest of Indian corn, wheat, peas, beans, squashes, and garden vegetables, and has made the forests to abound with game and the sea with fish and clams, and inasmuch as he has protected us from the ravages of the savages, has spared us from pestilence and disease, has granted us freedom to worship God according to the dictates of our own conscience.

Now I, your magistrate, do proclaim that all ye Pilgrims, with your wives and ye little ones, do gather at ye meeting house, on ye hill, between the hours of 9 and 12 in the day time, on Thursday, November 29th, of the year of our Lord one thousand six hundred and twenty-three and the third year since ye Pilgrims landed on ye Pilgrim Rock, there to listen to ye pastor and render thanksgiving to ye Almighty God for all His blessings.

William Bradford

Ye Governor of Ye Colony

Although I was uncomfortable contradicting my host, I felt compelled to tell him that this was a hoax. Can you figure out why? Its two short paragraphs are chock full of factual errors and anachronisms. The proclamation gives the wrong year for the celebration, to begin with. It refers to the colony’s “pastor,” although they didn’t have one for many years after settling in New England. It uses language and concepts unknown to the Pilgrims, most notably the reference to the dictates of conscience, an 18th-century Enlightenment concept that the Pilgrims would have roundly rejected. Comically, it alludes to “ye Pilgrim Rock,” a landmark unknown to the Pilgrims themselves and not mentioned for 120 years after they landed.

This obvious fabrication has been circulating in the United States for decades. The earliest publication of it that I have come across is from the Chicago Daily Tribune in November 1939, and it may actually be much older. More recently, in 1985 a White House speechwriter quoted from it in one of Ronald Reagan’s presidential Thanksgiving proclamations. Since that time it has appeared (in whole or in part) in at least three books published by reputable presses, and it thrives on the internet, where it is reproduced ad infinitum.

The origin of this clumsy hoax will probably always be a mystery. Why it has gained so much credence is easier to fathom: a lot of us want to believe it. I don’t mean that we consciously embrace something we know to be false. That’s probably pretty rare. The temptation that most of us face is not to dishonesty but to what I would call willful gullibility—the readiness to accept uncritically what we want to be true.

So, for example, Christians longing for firm evidence of America’s religious roots will find much to admire in the spurious proclamation. Whereas the William Bradford who authored Of Plymouth Plantation did not even mention the First Thanksgiving, the Bradford who penned this imaginary decree reassures us with comforting detail. Leaving no doubt about the Christian underpinnings of the holiday, he expresses special gratitude for religious freedom and enjoins the Pilgrims to “render thanksgiving to ye Almighty God for all his blessings.”

It is no coincidence, I think, that most of the internet sites posting the proclamation are sponsored by Christian organizations, or that it lives on in books with titles like America’s God and Country or Putting God Back into the Holidays. Not all of these organizations or authors are seeking ammunition for the culture wars—several simply want to encourage other Christians—but all share a (likely unconscious) willingness to suspend their critical faculties when they find historical evidence that serves their purposes. Make no mistake: this is a tendency we’re all prone to.

“Ye pilgrims”, “ye little ones”, “ye meeting house”, “ye hill”…Too many “ye’s” in this document to be believable.

Pingback: Thanksgiving – The Personal Pretensions of a Catholic Hamilton

Undoubtedly, The Lord has chosen to keep most of the past hidden from us.

Conversely, what is preserved is all the more important,